Introduction and Background

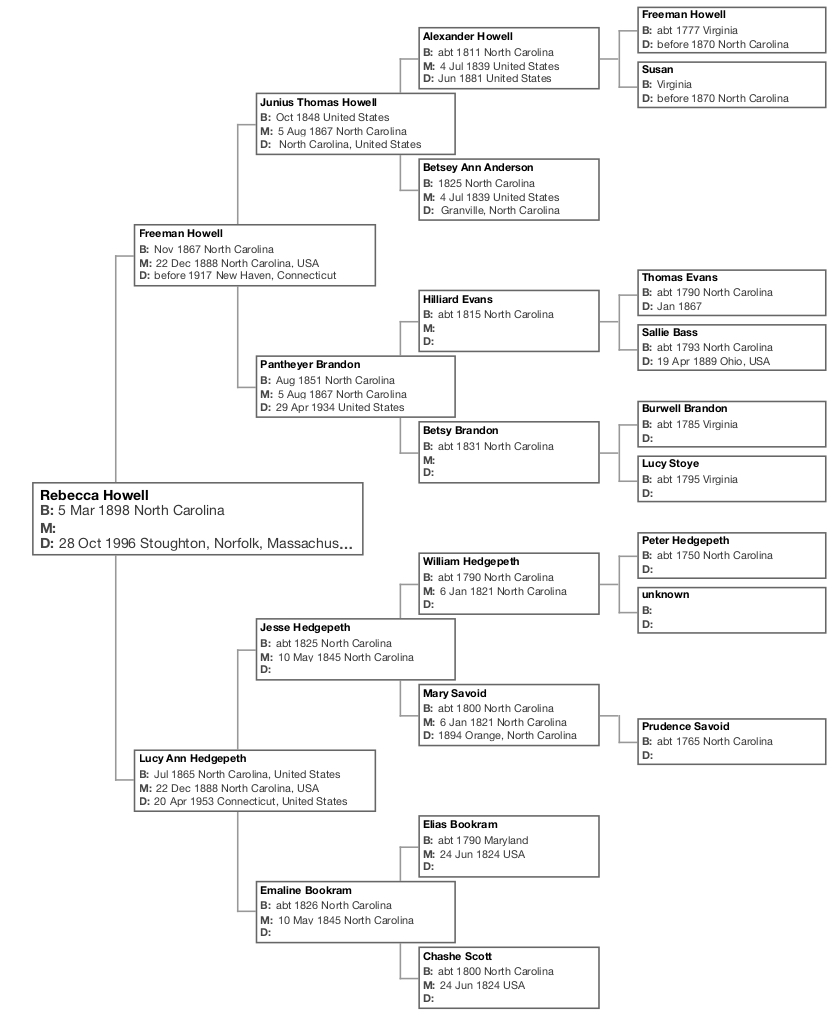

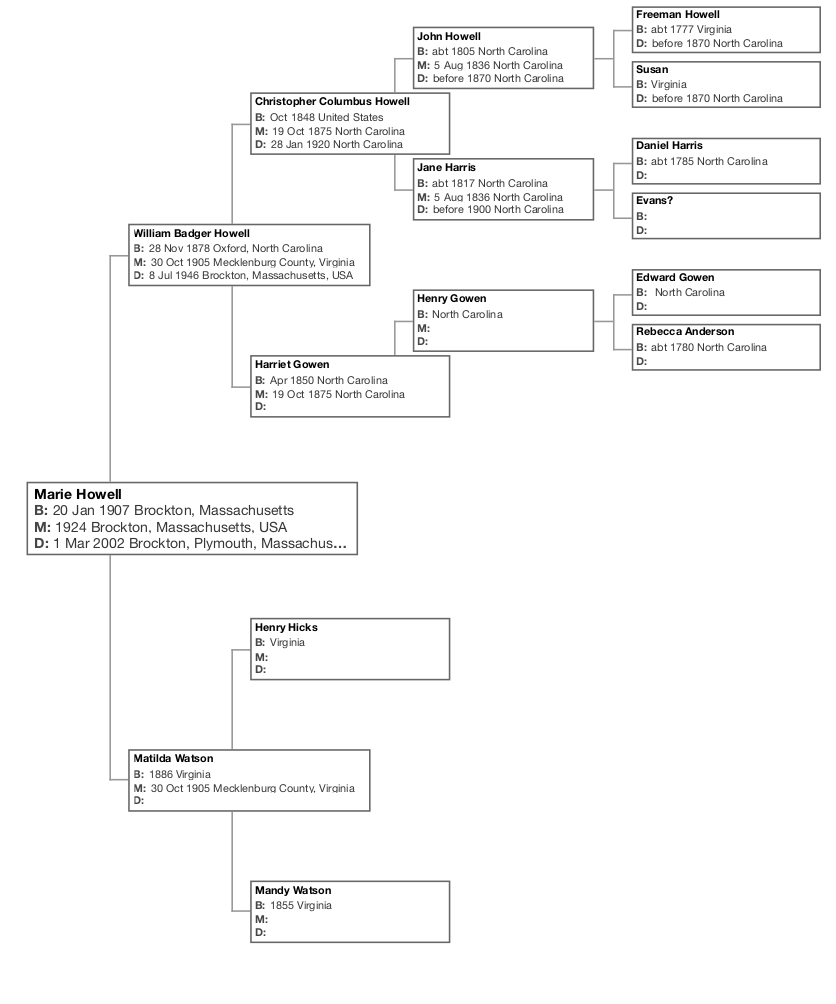

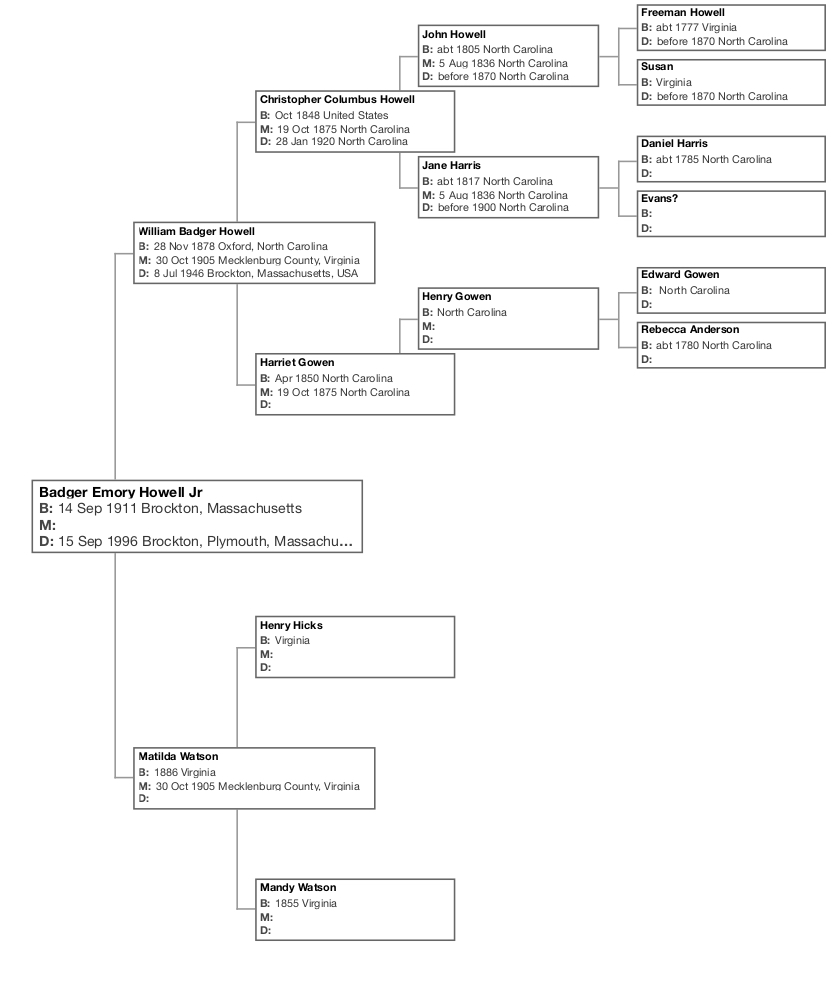

Residing in Granville County were two free born women of color named Polly Ann Howell. These women were also first cousins, very close in age and their families often lived on adjoining properties. As a result, the records for both women can be mixed up if a thorough examination of the records is not performed. First there was Polly Ann Howell (born 1840) who was the daughter of Alexander “Doc” Howell and Betsy Ann Anderson. And second there was Polly Ann Howell (1844-1914) who was the daughter of John Howell and Jane Harris. Alexander Howell and John Howell were brothers, making their children first cousins. By carefully creating timelines based upon a deep analysis of primary source records, it is possible to differentiate between the two women in the archives.

Polly Ann Howell (daughter of Alexander Howell and Betsy Ann Anderson)

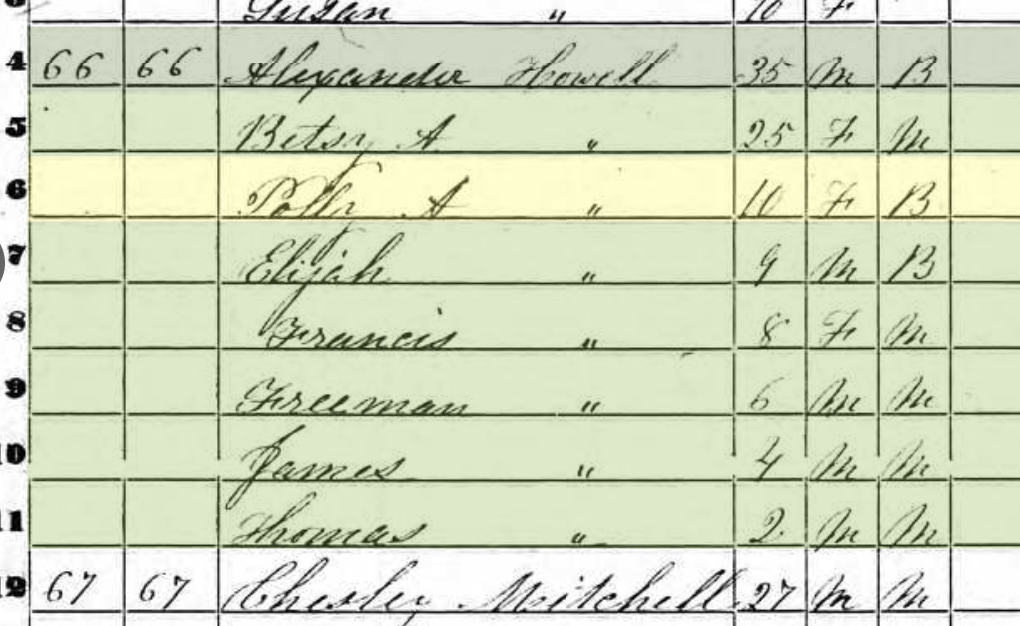

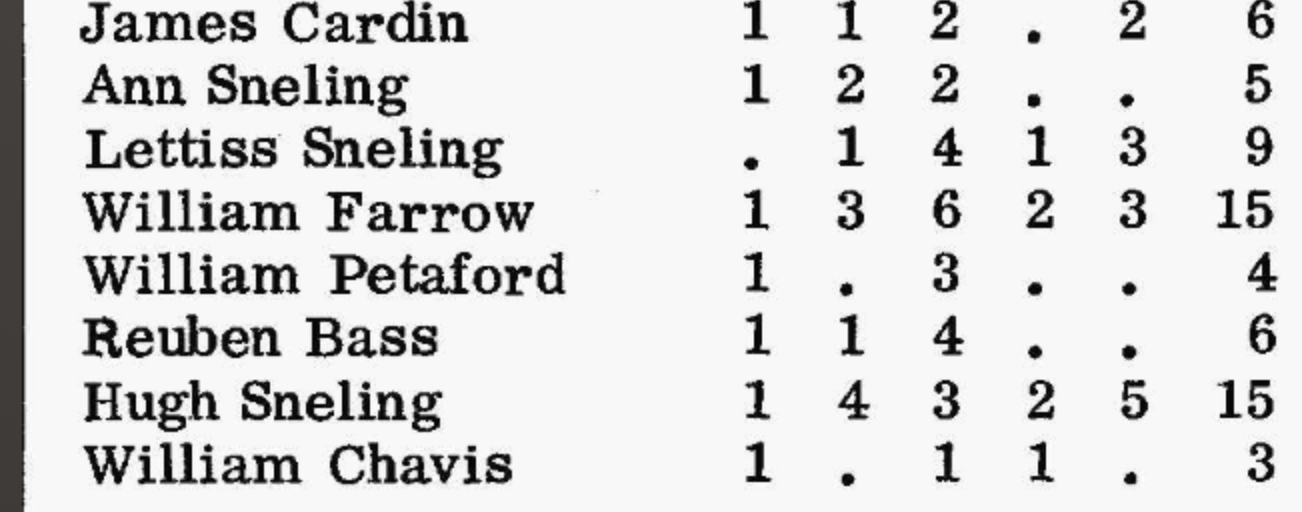

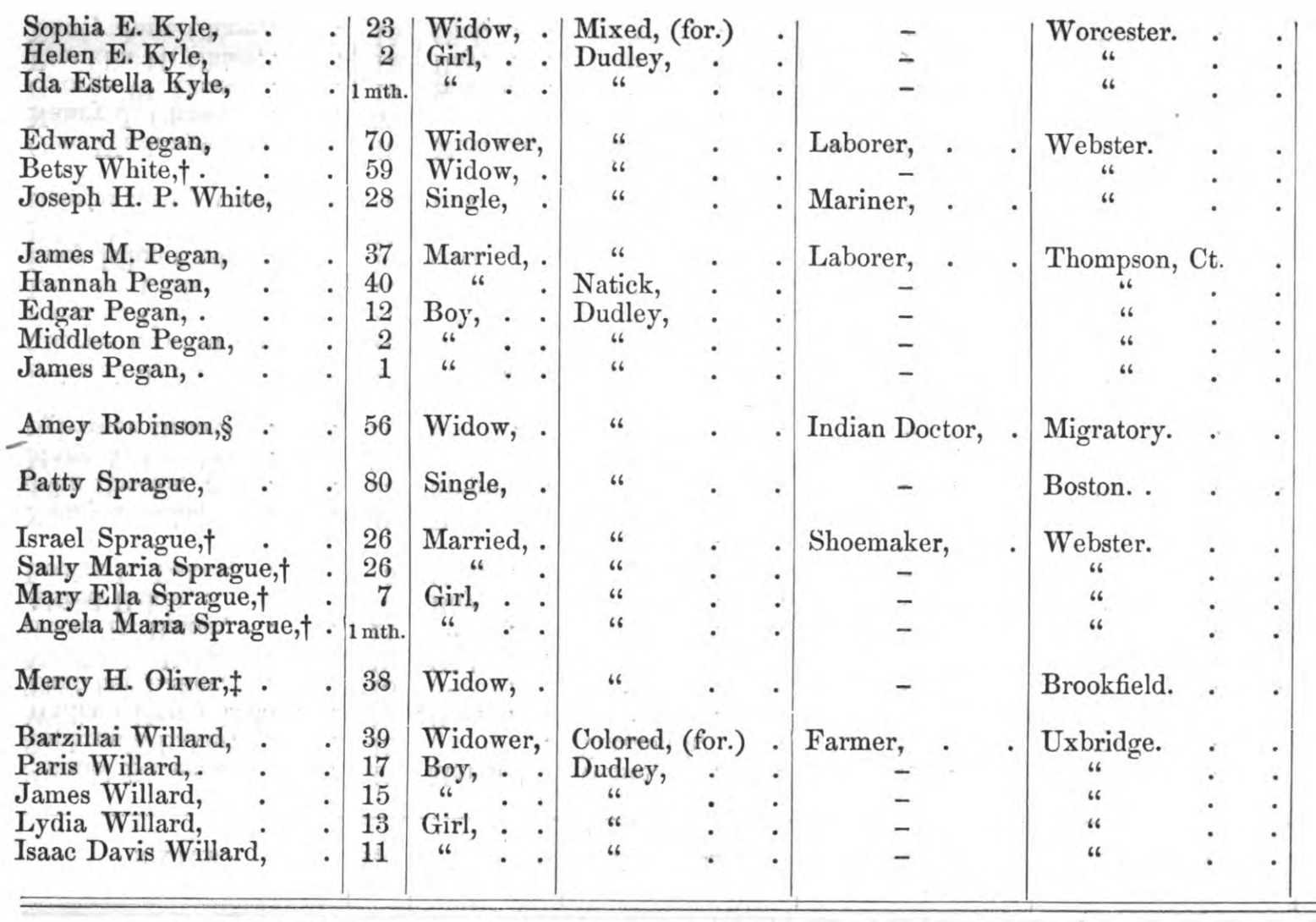

In the 1850 census for Tabs Creek district, Polly Ann Howell, age 10, is found residing in a household headed by her father Alexander Howell:

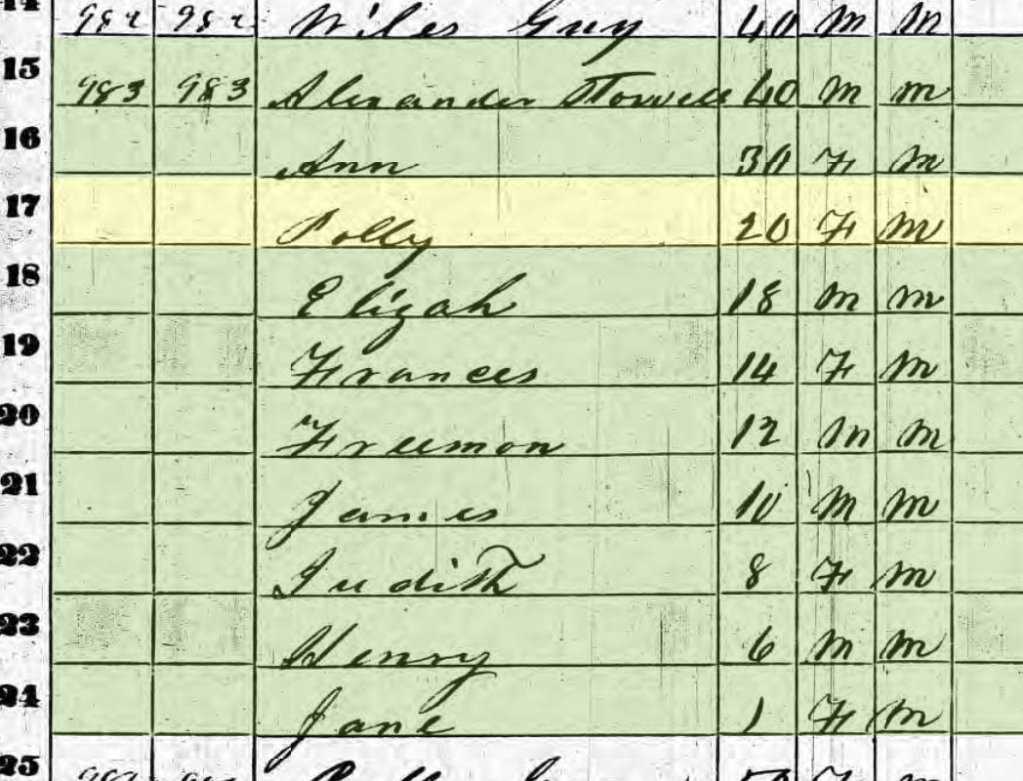

In the 1860 census, Polly Ann Howell is again found residing in a household of her father Alexander Howell in Tabs Creek district:

This is the last census record that Polly Ann Howell appeared in. If it was not for the records of her son Ben Howell (1867-1946), not much else would be known about her life. Polly Ann Howell does not appear in her parent’s household in the 1870 or 1880 census, indicating that she likely passed away around this time.

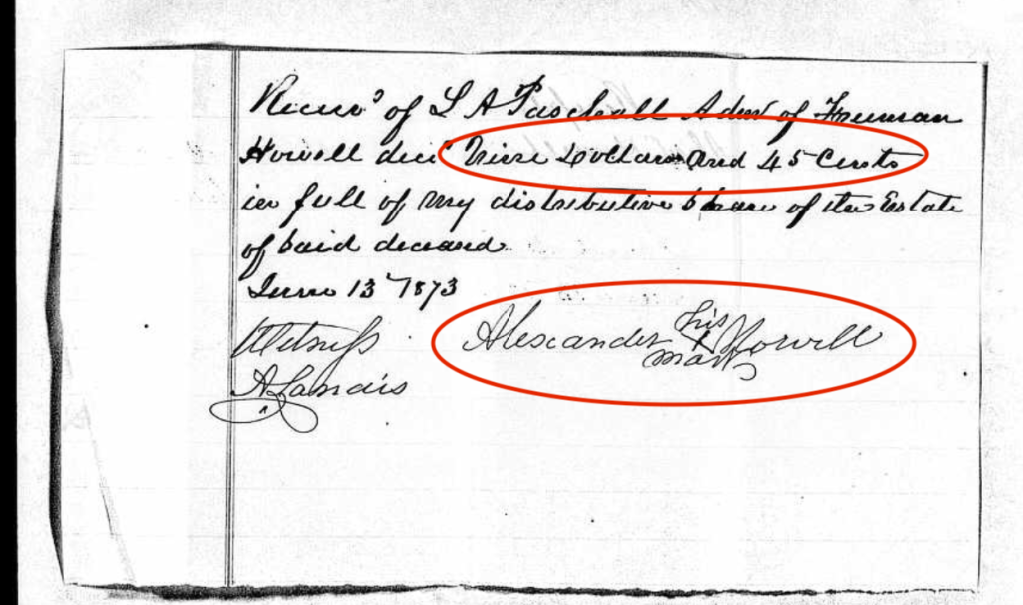

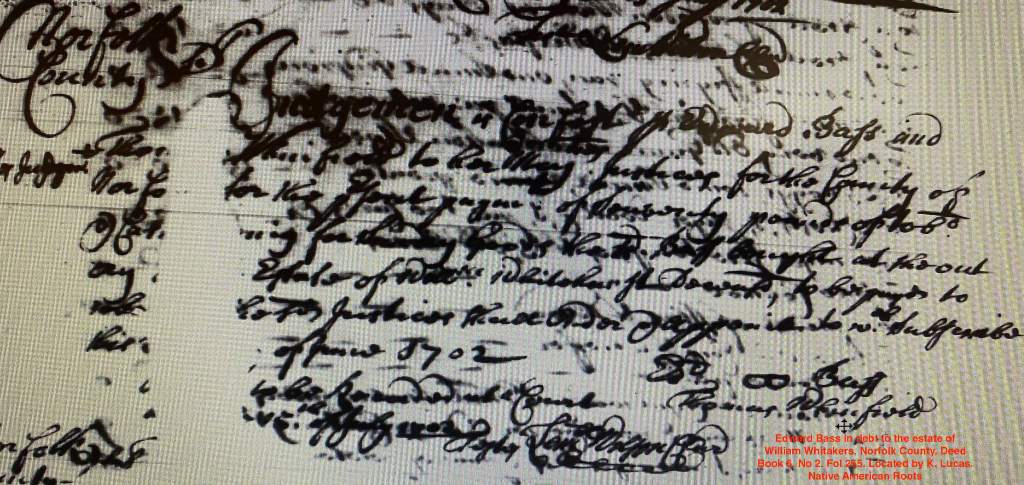

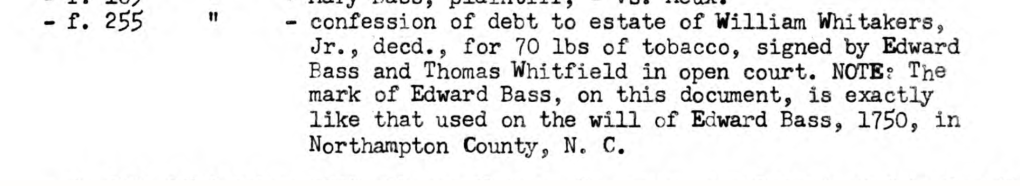

On 13 June 1873, Polly Ann Howell’s father Alexander Howell received a full $9.45 share from his deceased father Freeman Howell’s estate. This document establishes that the Polly Ann (Howell) Curtis who received an 85 cent payout from the estate cannot be the daughter of Alexander Howell. This is discussed in more detail later.

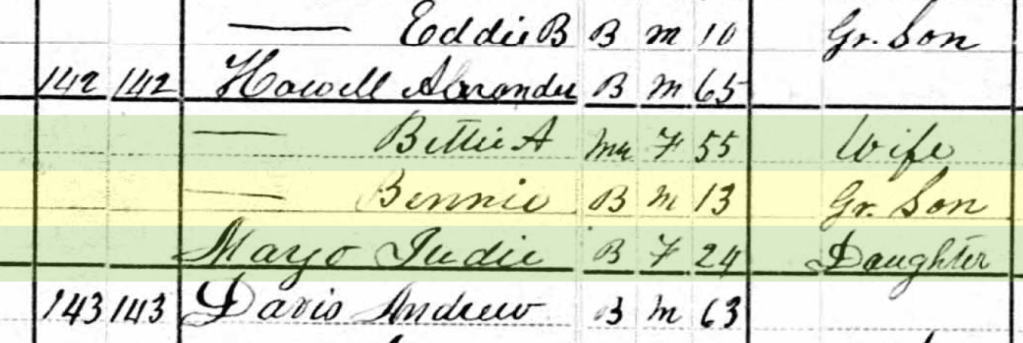

In the 1880 census, a 13 year old boy named “Bennie Howell” is identified as a grandson of head of household Alexander Howell. No person in the household is identified as the parent of Ben. This is typically indicative of Ben Howell having been orphaned or removed from his parents and being raised by his grandparents.

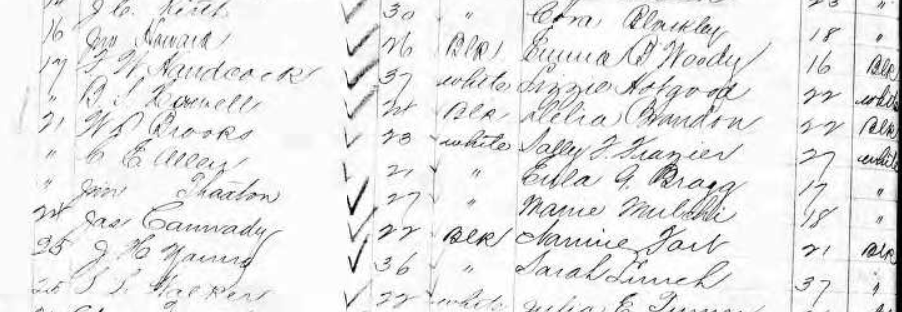

Ben “Bennie” Howell married Delia Brandon on 11 Dec 1891. In that record he is called “B J Howell”:

Original data:North Carolina County Registers of Deeds. Microfilm. Record Group 048. North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, NC.

In the subsequent 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930, 1940 census, Ben Howell is consistently enumerated in the Fishing Creek district and with the surname Howell. He is not ever referred to as having the surname Curtis.

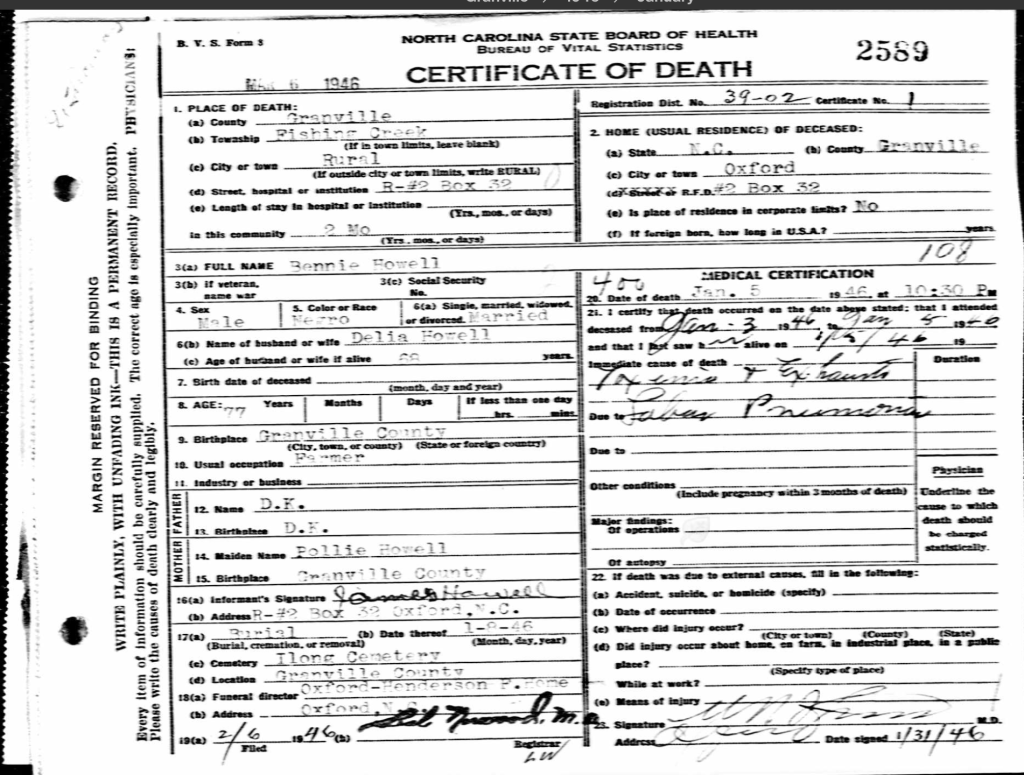

On 5 January 1946, Ben Howell passed away and his death certificate provides direct information on the identity of his parents. The informant on the death certificate was Ben Howell’s son James Howell (1894-1979). So he was the person who provided the biographical information about his father Ben Howell. In the place of the decedent’s father, is written “D K” for both name and birth place. “D K” is shorthand for “Don’t Know”. In the place of the decedent’s mother, is written “Pollie Howell” for the name and “Granville County” for birthplace.

The death record combined with the information learned from the 1880 census in which Ben Howell is identified as a grandson of Alexander Howell, informs us that Ben Howell was the son of a woman named Polly Howell who was the daughter of Alexander Howell. The 1850 and 1860 census enumerations of Alexander Howell’s household shows he had a daughter named Polly Ann Howell. These records consistently show that Ben Howell (1867-1946) was the son of Polly Ann Howell (born 1840). In every census record and on his marriage and death certificates, Ben Howell is never identified as having the surname Curtis or being the son of a man with the surname Curtis.

But what about the identity of his father? Ben Howell’s surname was “Howell”, the surname of his mother. If his mother was legally married at the time of his birth which occurred circa 1867, then he would take the surname of his father. However Ben Howell took his mother’s surname, meaning he was born out of wedlock. This is consistent with James Howell indicating that he did not know the name of Ben Howell’s father as shown on the death certificate. It is incredibly difficult to find documentation that identifies the father of children born out of wedlock. To date, Ben Howell has not been located in the 1870 census. The 1870 census was the first census in which all residents, free born and formerly enslaved, were fully enumerated by name. As a result, there was a major undercount in the 1870 census in which many households and individuals were skipped over. If Ben Howell was enumerated in the 1870 census and that record could be found, it may help to identify his father. Ben Howell would have been approximately 3 years old in 1870. Other avenues of research are with genetic genealogy. Direct male descendants of Ben Howell can do a y-DNA test which specifically tests the y-DNA information that is passed down solely from father to son uninterrupted. The direct male descendants of Ben Howell will carry the y-DNA of his father, thus making it possible to find y-DNA matches. Family Tree DNA (FTDNA) offers the best tests at different price points (the more markers tested, the better the accuracy):

https://www.familytreedna.com/products/y-dna

Polly Ann Howell (daughter of John Howell and Jane Harris)

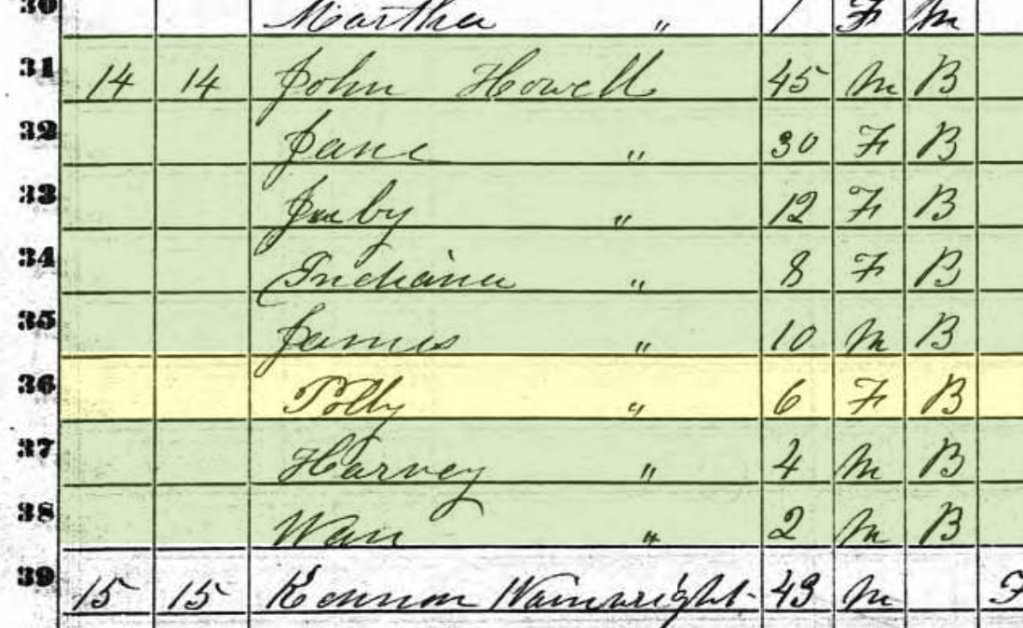

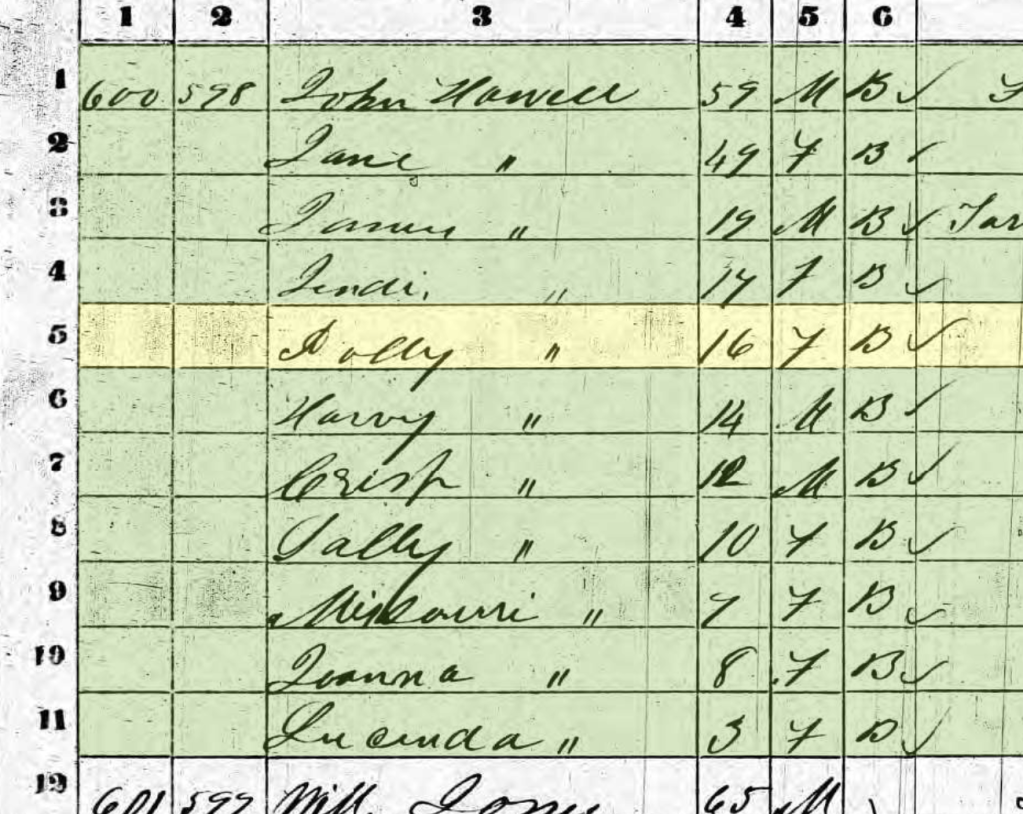

In the 1850 census for the Tar River district, Polly Ann Howell, age 6, is enumerated in the household of her father John Howell.

In the 1860 census for the Oxford district, Polly Ann Howell, age 16, is again enumerated in the household of her father John Howell.

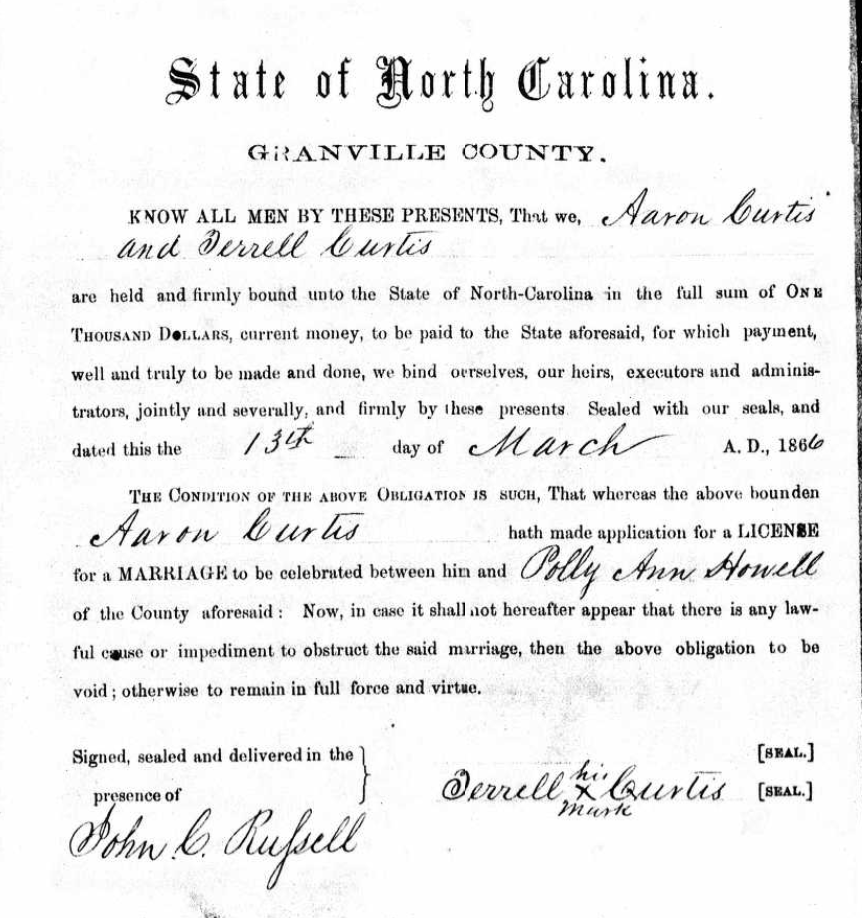

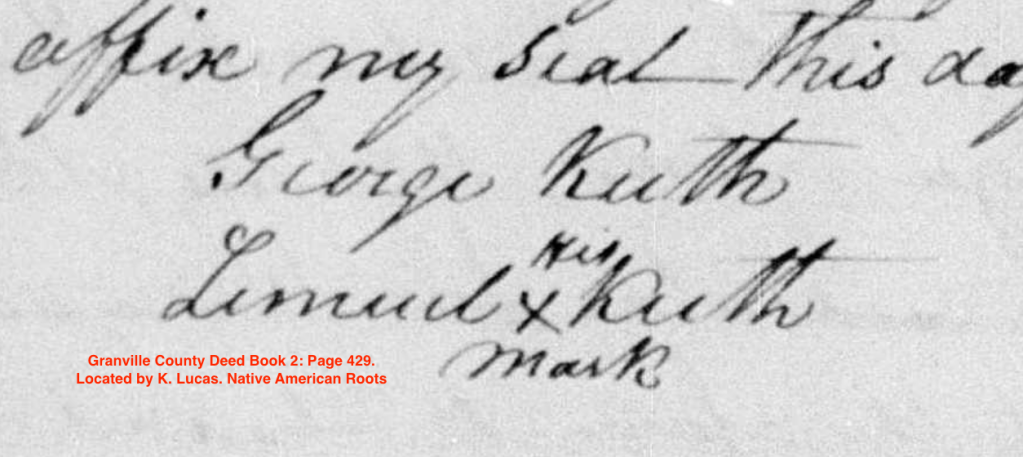

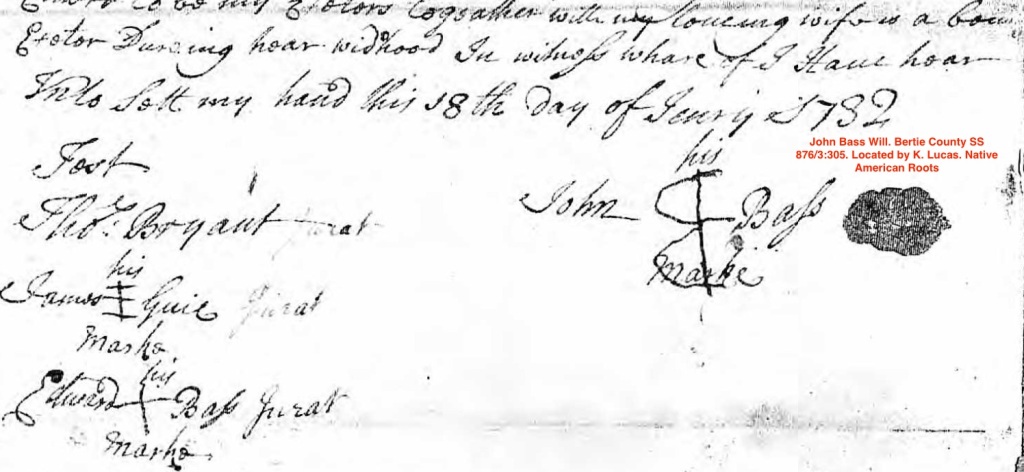

On 13 March 1866, Aaron Curtis and his brother Terrell Curtis filed a marriage bond for Aaron Curtis’ marriage to Polly Ann Howell.

Original data:North Carolina County Registers of Deeds. Microfilm. Record Group 048. North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, NC.

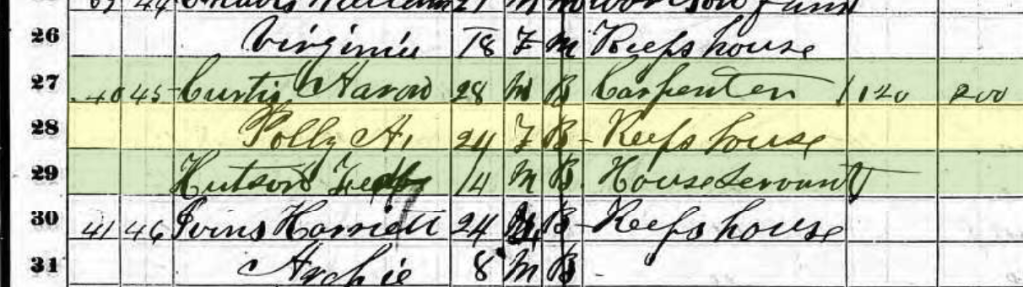

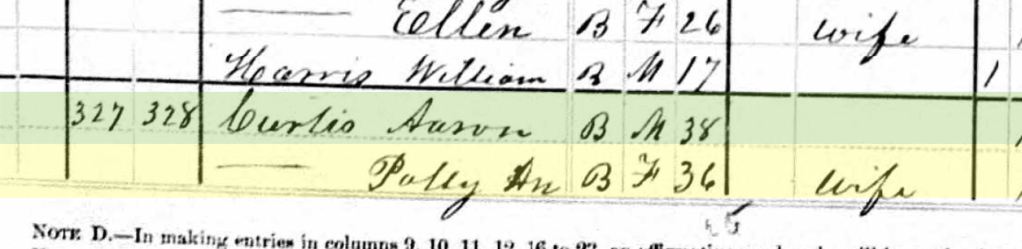

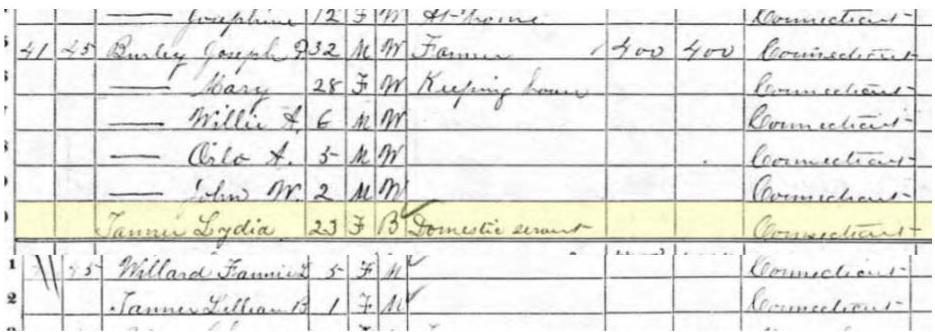

In the 1870 census, Polly Ann Howell, now 4 years married to Aaron Curtis is enumerated as “Polly A Curtis”, age 24, in the household of her husband Aaron Curtis. Please note there are no children residing in their household. Ben Howell was 3 years old at this time and is not found in their household.

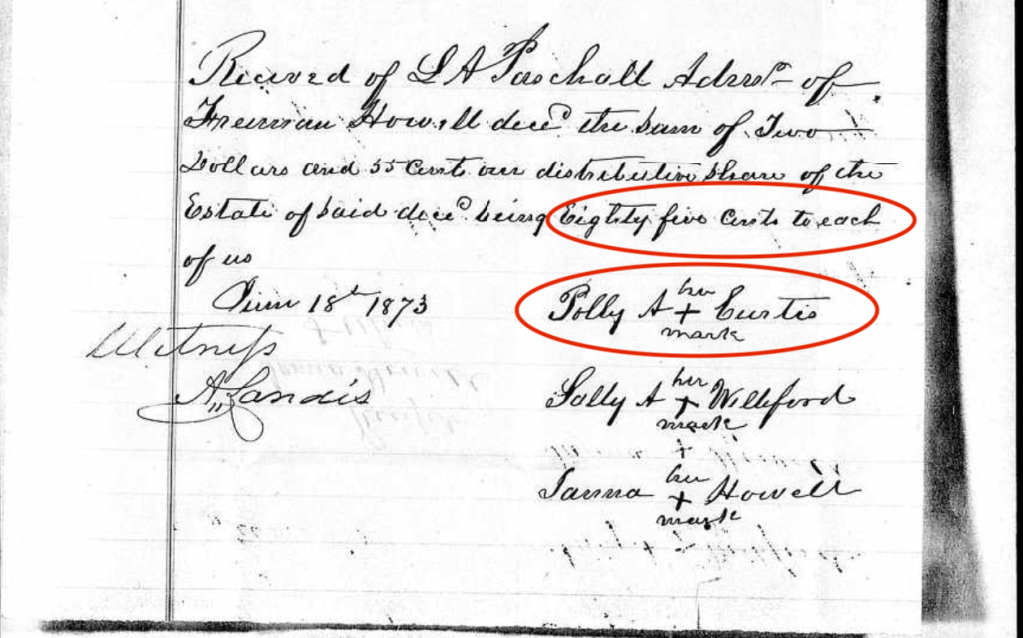

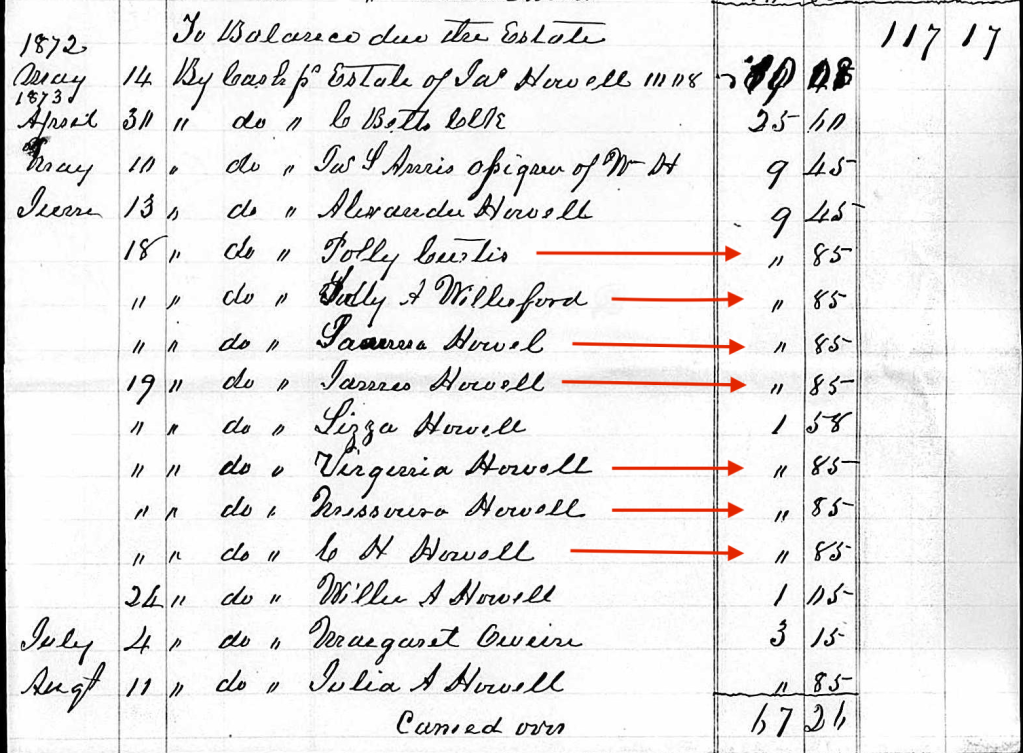

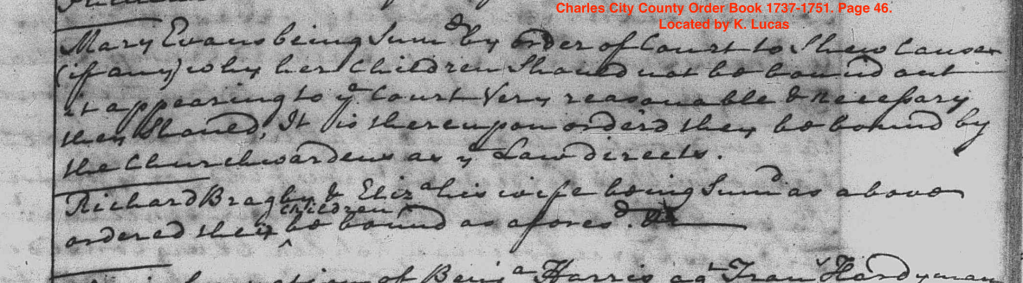

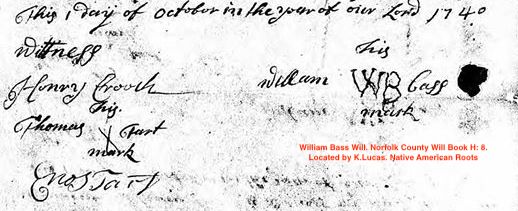

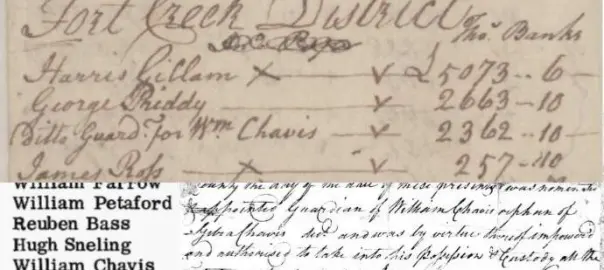

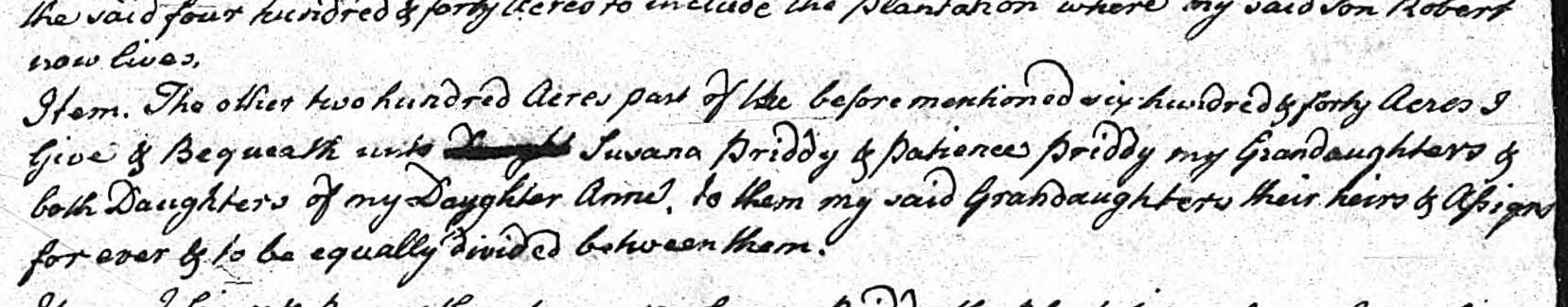

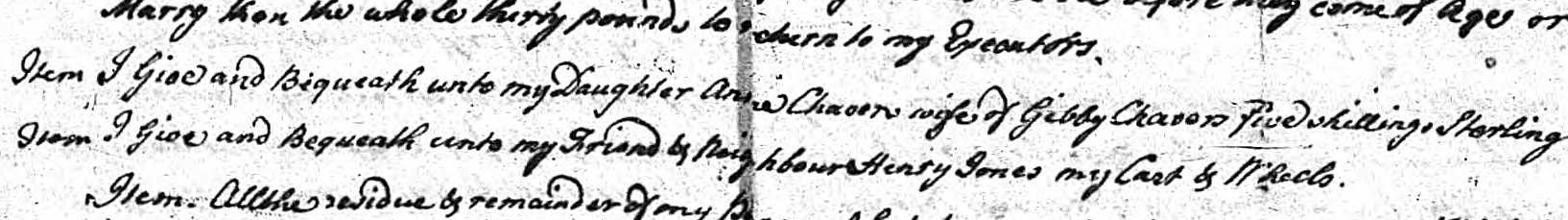

On 18 June 1873, Polly Ann Howell, now known as Polly Ann Curtis received 85 cents as a legatee of her grandfather Freeman Howell’s estate. By 1870 Freeman Howell had passed away and his estate was divided among his living heirs. Each surviving child of Freeman Howell received a share of $9.45. If that child was deceased and had living children, then that $9.45 is equally divided among those children. This is why Freeman Howell’s son Alexander Howell who was still alive, received a full $9.45 and none of Alexander Howell’s children received a share. On the other hand, John Howell pre-deceased his father Freeman Howell. Therefore John Howell’s share of $9.45 was equally divided among his 11 living children. As a living daughter of John Howell, Polly Ann (Howell) Curtis was entitled to 85 cents. The following receipt and account included in Freeman Howell’s estate records show that Polly Ann (Howell) Curtis and two of her sisters, Sally (Howell) Williford (she was married to Lunsford Williford) and Joanna Howell all received their 85 cent share on the same day. This is direct confirmation through primary source records that the Polly Ann Howell who married Aaron Curtis was the daughter of John Howell.

Source: Granville County, North Carolina, Estate Records; Author: North Carolina. Probate Court (Granville County); Probate Place: Granville, North Carolina

Source: Granville County, North Carolina, Estate Records; Author: North Carolina. Probate Court (Granville County); Probate Place: Granville, North Carolina

In the 1880 census, Polly Ann Howell, still married to Aaron Curtis is enumerated as “Pollyann Curtis” in the household of her husband Aaron Curtis. Please note there are no children in their household. In 1880, Ben Howell was 13 years old and residing in the household of his grandfather Alexander Howell.

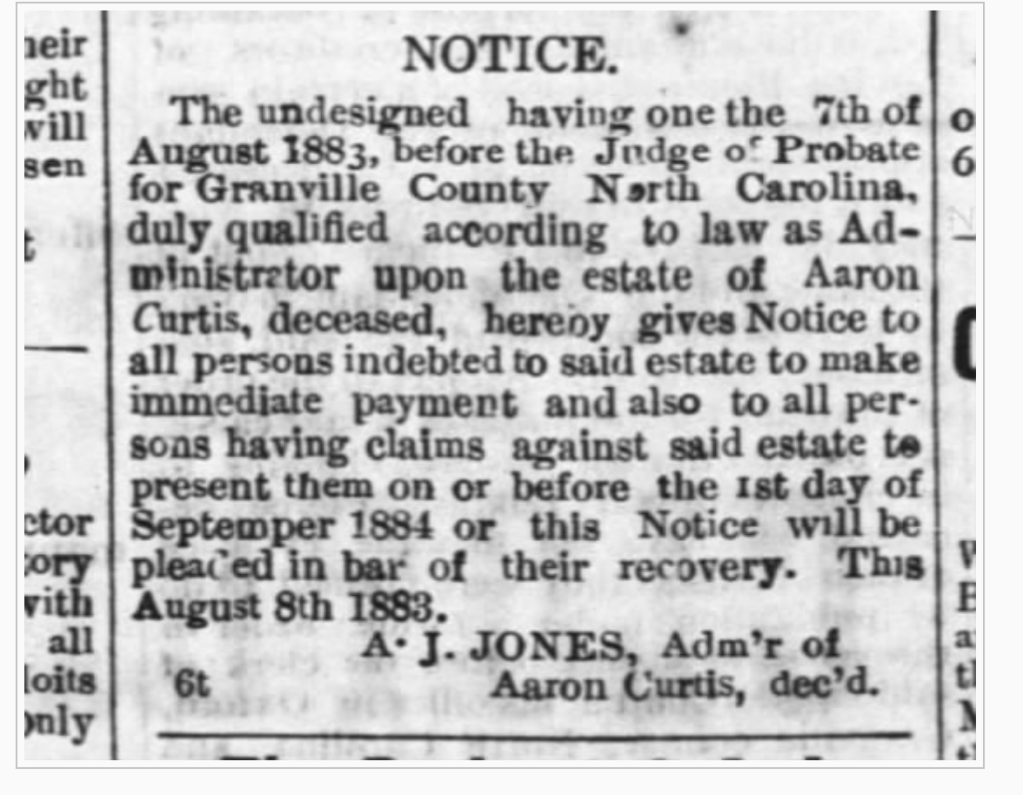

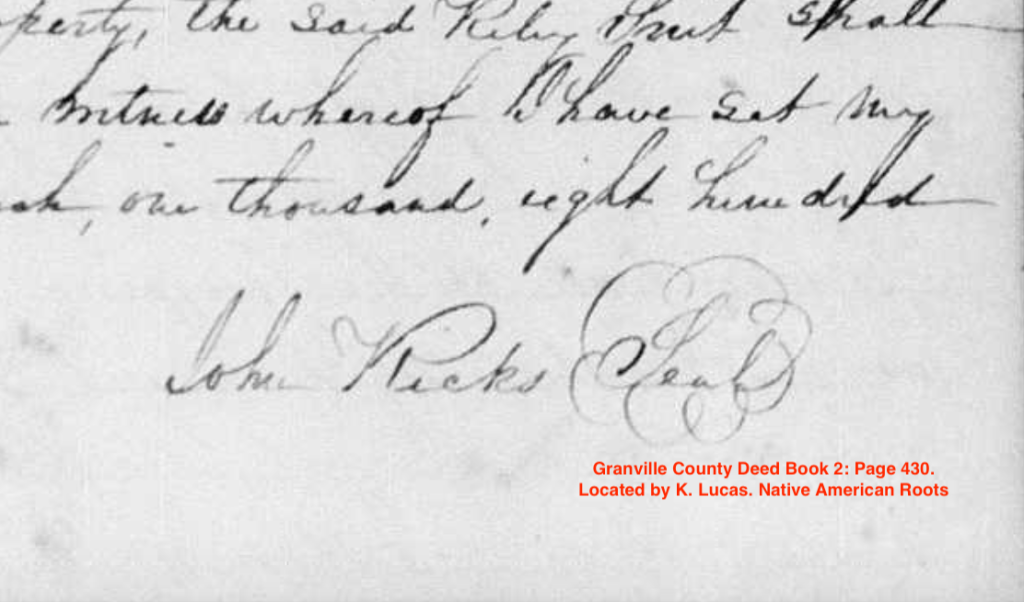

Though he died decades before North Carolina issued death certificates, there is a lot of documentation of when Aaron Curtis died because his estate records were filed with the court. In 1883, the administrator of his estate, A.J. Jones, filed a notice in the newspaper as required by law:

Source:The Torchlight. Oxford, North Carolina. 28 Aug 1883, Tue

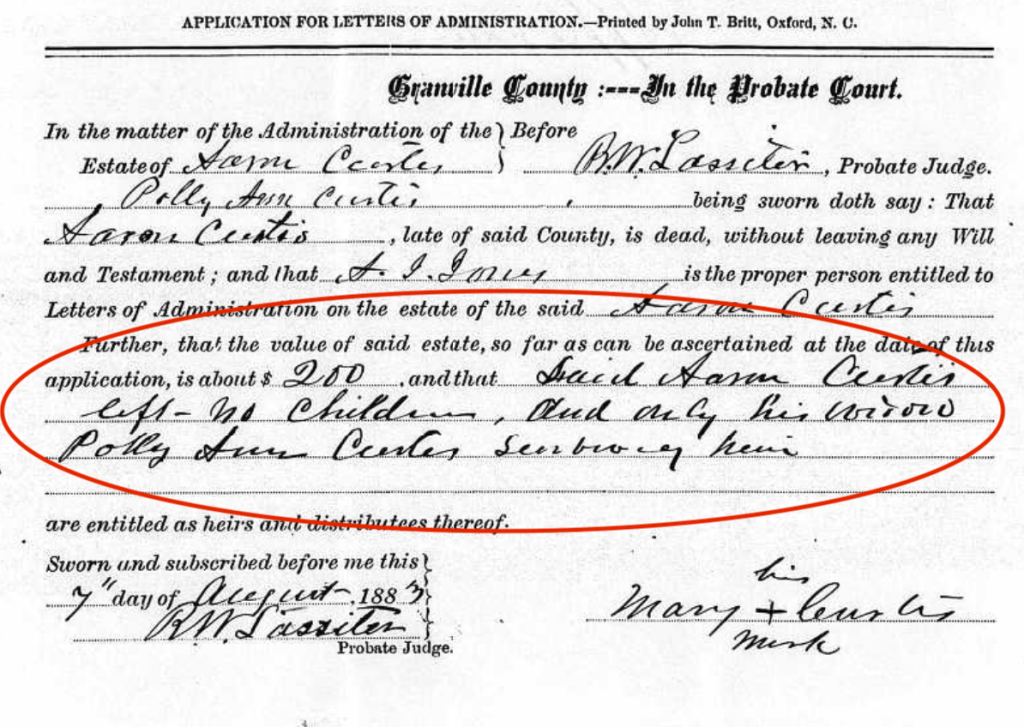

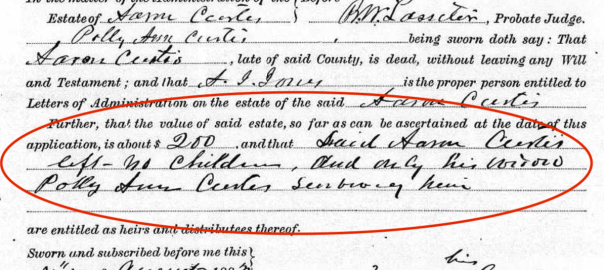

Aaron Curtis’ extensive estate records are digitized and available to review on Ancestry. The documents outline that Aaron Curtis had one surviving spouse – Polly (also called Mary; Polly and Mary are the same name) and no surviving children. If Ben Howell was a son of Aaron Curtis he would certainly be named in the estate records. The records make it clear that Aaron Curtis did not have any children which is consistent with the 1870 and 1880 census enumerations which showed no children in his household.

Source: Granville County, North Carolina, Estate Records; Author: North Carolina. Probate Court (Granville County); Probate Place: Granville, North Carolina

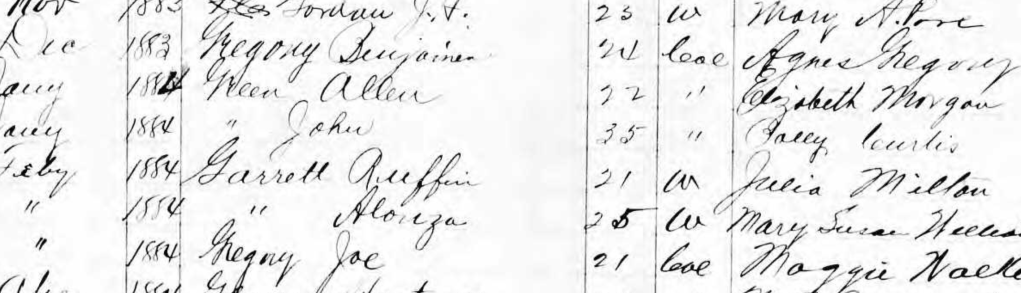

Widowed in 1883 at the age of 39, Polly Ann Howell’s story did not end there. The following year on 17 Jan 1884, Polly Ann Howell married John Green. In the marriage record she is referred to by her first married name – Polly Curtis.

Original data:North Carolina County Registers of Deeds. Microfilm. Record Group 048. North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, NC.

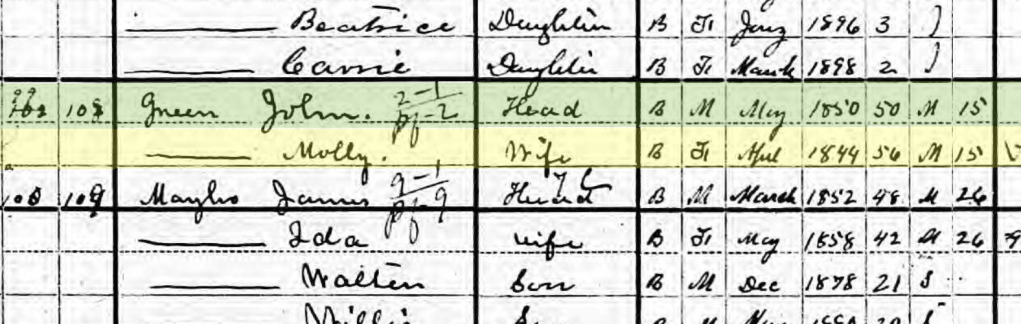

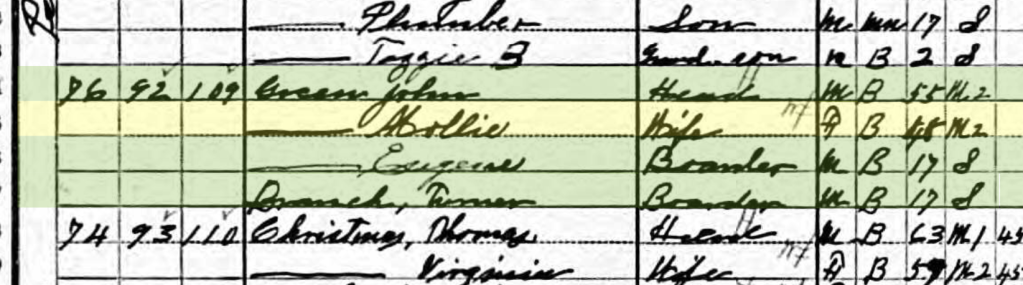

In the 1900 census for the Oxford district, Polly Ann Howell now married to John Green is enumerated as “Molly Green”, age 56 in the household of her husband John Green. The enumerator documents that they have been married for approximately 15 years which is consistent with the date of the 1884 marriage record. “Molly” is a common nickname for Polly/Mary. See: https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Traditional_Nicknames_in_Old_Documents_-_A_Wiki_List

In the 1910 census, Polly Ann Howell, still married to John Green is again enumerated as “Mollie Green” in the household of her husband John Green. The enumerator even noted that Polly Ann Howell was currently in her second marriage as noted by the “M2” notation for her marriage status. This is again consistent with Polly Ann Howell first marrying Aaron Curtis and second marrying John Green.

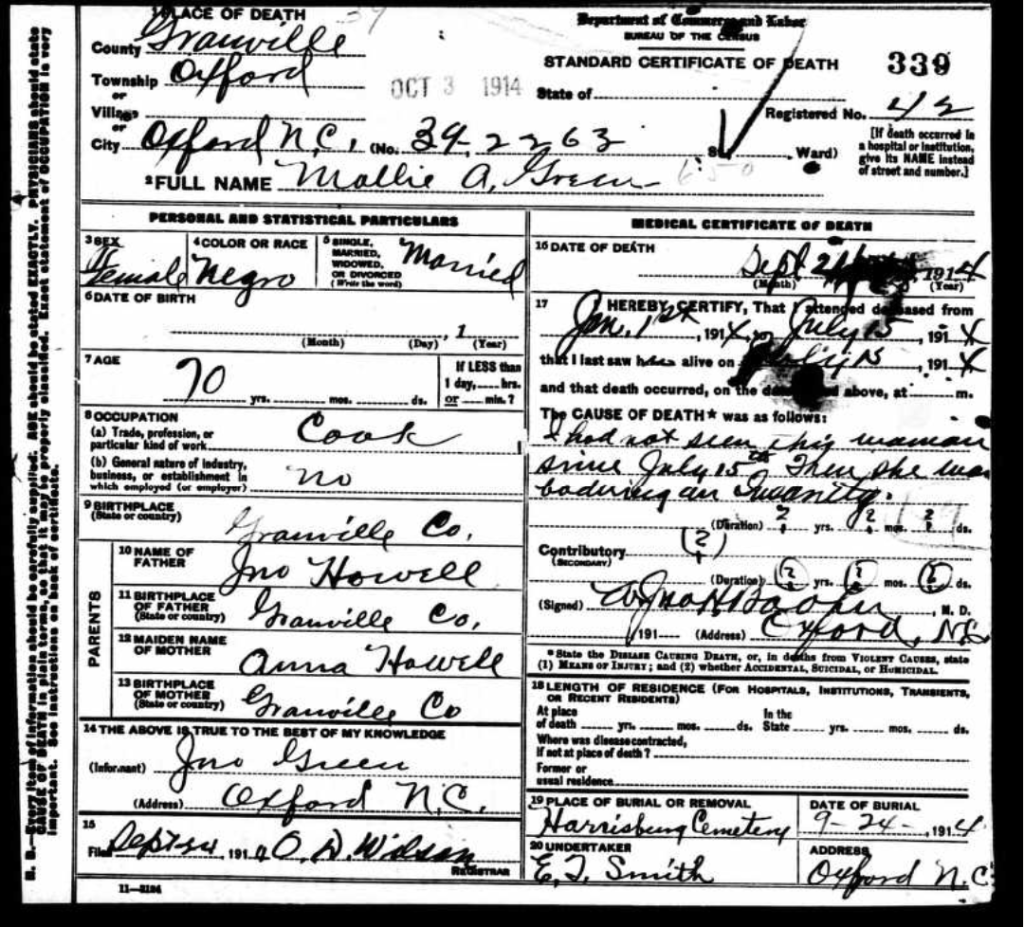

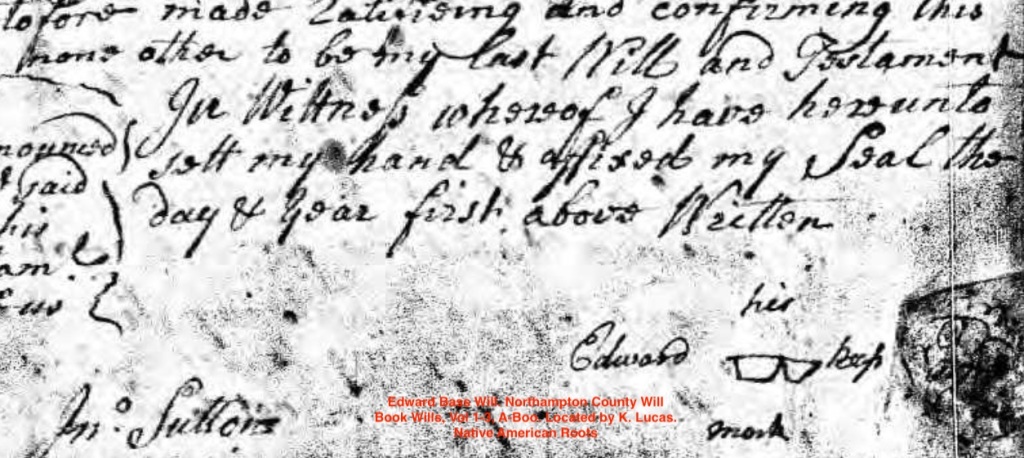

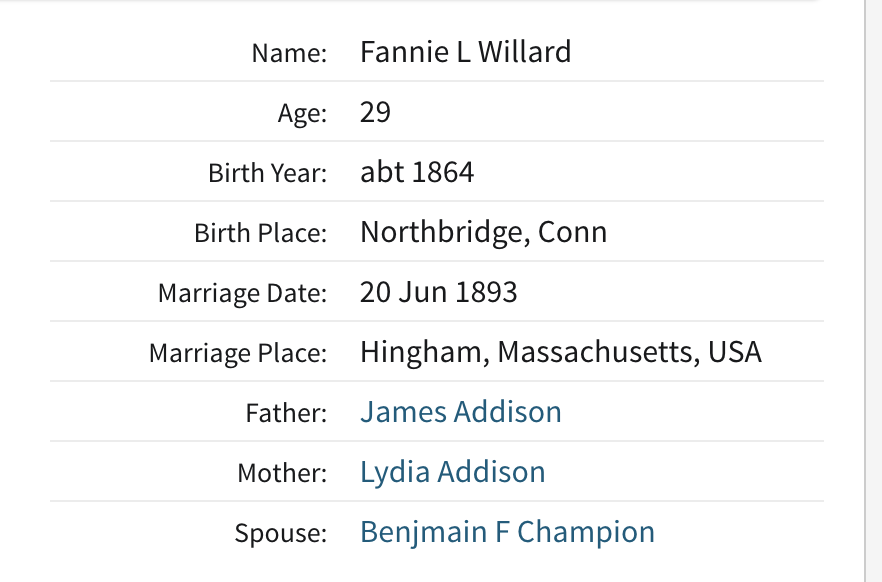

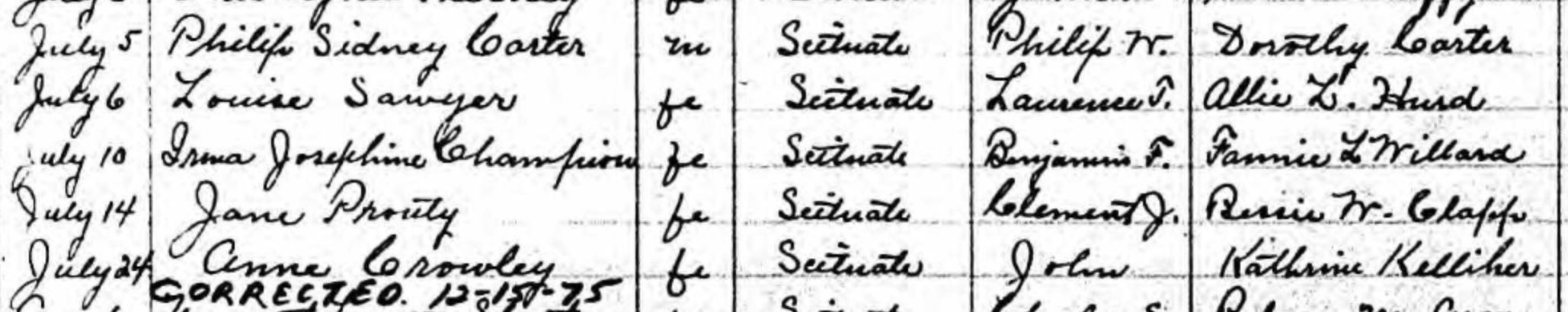

Polly Ann Howell died on 21 Sep 1914 at the age of 70 as “Mollie A Green”. Her death certificate provides additional corroboration of her identity. Her husband John Green is identified as the informant of the death certificate. Her parents are identified as John and Anna Howell. John Howell’s wife was named Jane so the incorrect identification of “Anna” may be a mistake or misinformation from John Green. But most importantly he correctly identifies Polly Ann Howell’s father as John Howell.

Original data:North Carolina State Board of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics. North Carolina Death Certificates. Microfilm S.123. Rolls 19-242, 280, 313-682, 1040-1297. North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, North Carolina.

Final Analysis

The primary source evidence presented above demonstrates that the Polly Ann Howell (1844-1914) who married Aaron Curtis in 1866, was the daughter of John Howell and Jane Harris. When Aaron Curtis died in 1883, his estate records unequivocally state that he had a surviving spouse named Polly Ann Curtis and that he had no surviving children. The following year in 1884, Polly Ann Howell, recently widowed, married for a second time to John Green. Her death record filed in 1914 clearly identified her as the daughter of John Howell. Additionally, Freeman Howell’s estate records firmly establish that the Polly Ann (Howell) Curtis who received 85 cents from the estate was the daughter of John Howell who was deceased.

The other Polly Ann Howell (born 1840) who was the daughter of Alexander “Doc” Howell and Betsy Ann Anderson had one son born out of wedlock named Ben Howell and because he was born out of wedlock, he was given his mother’s surname – Howell. There are no records located to date which identify Ben Howell’s father. Aaron Curtis cannot be Ben Howell’s father because Aaron Curtis’ estate records directly state he had no surviving children. This is confirmed by the judge, estate administrator, and the widow.

I hope descendants and researchers will update their family trees with the correct information so that none of the Howell family member are left out. It is important we present accurate information for future generations

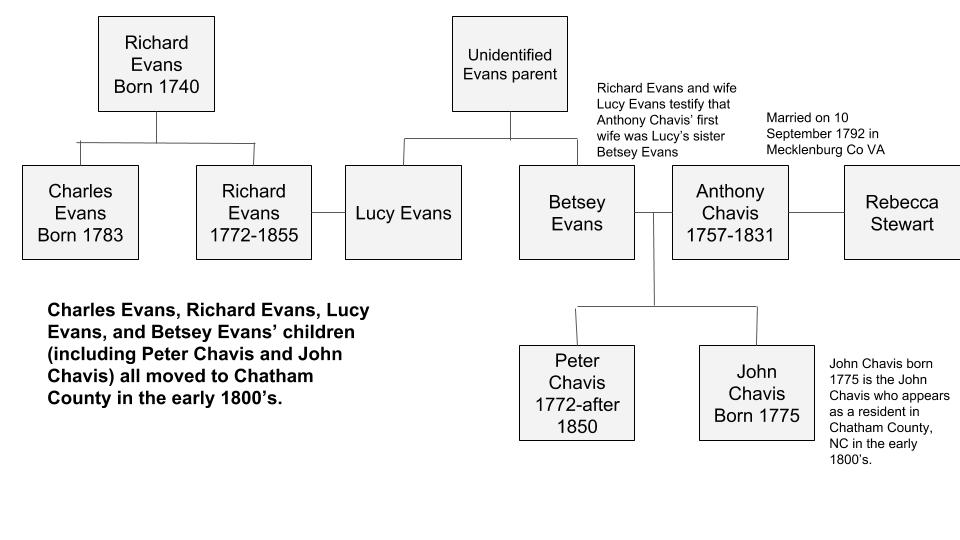

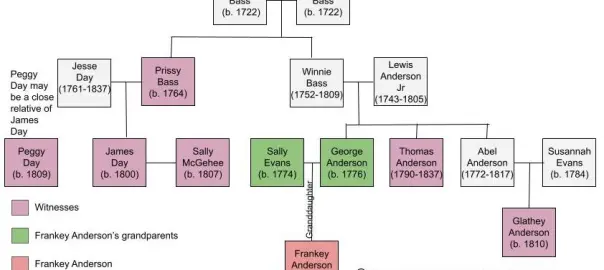

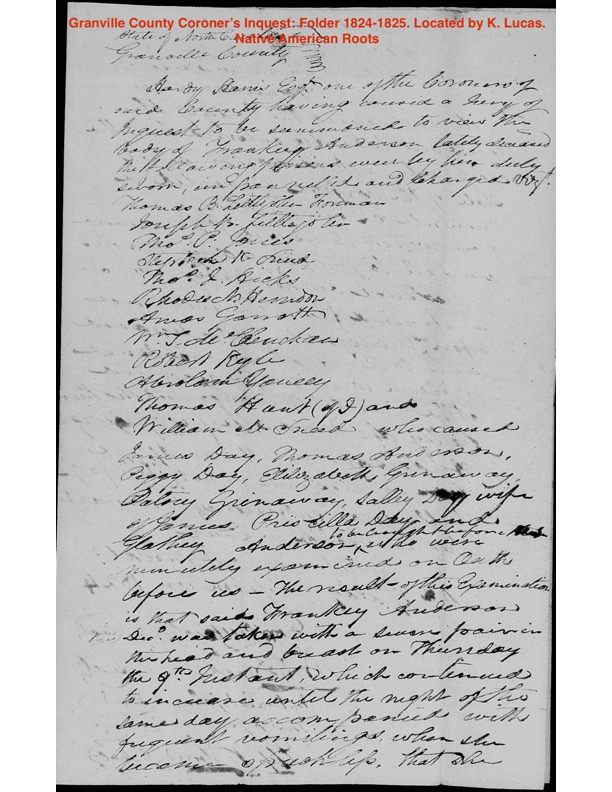

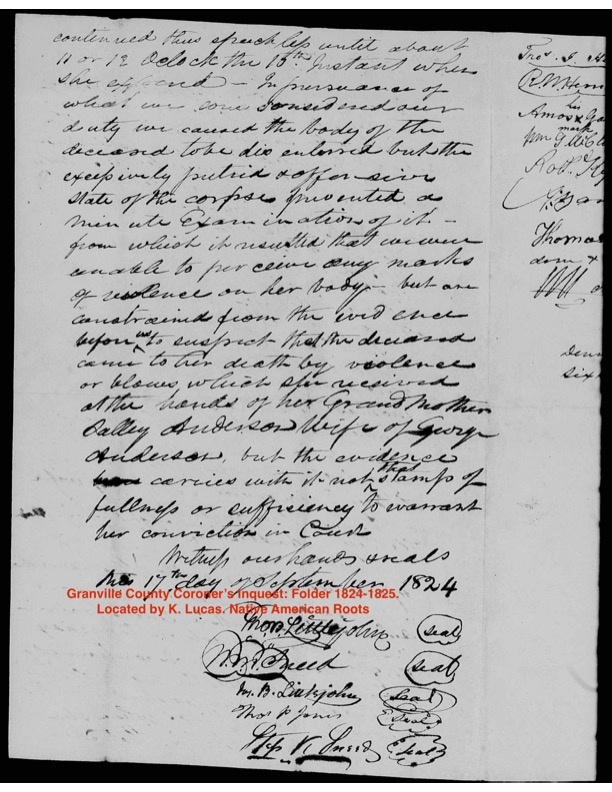

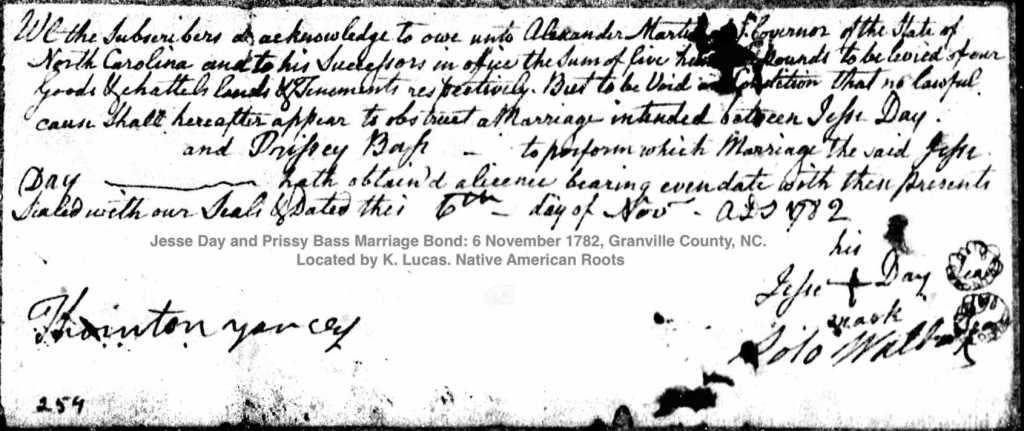

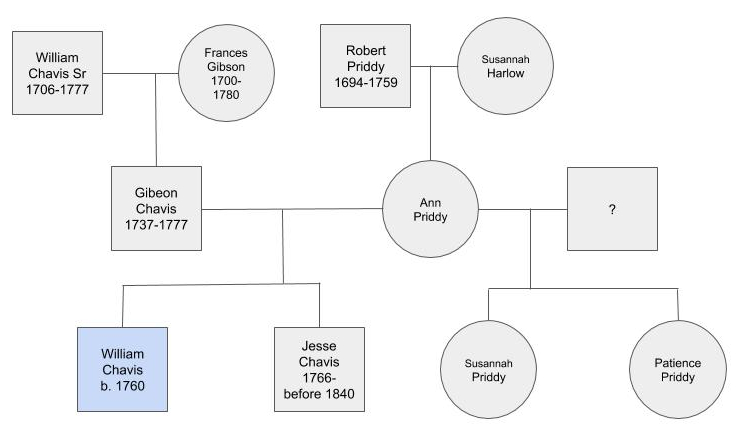

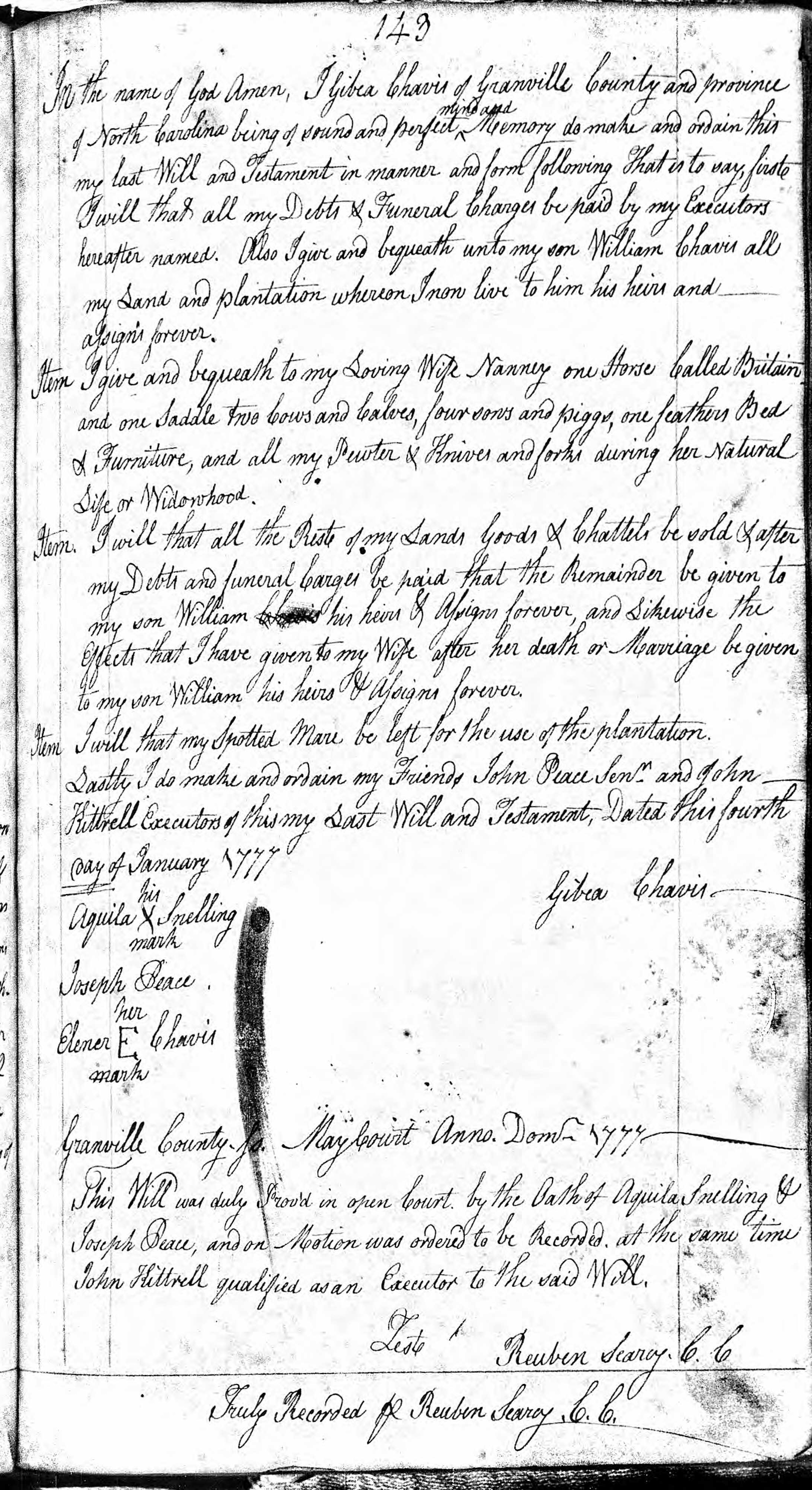

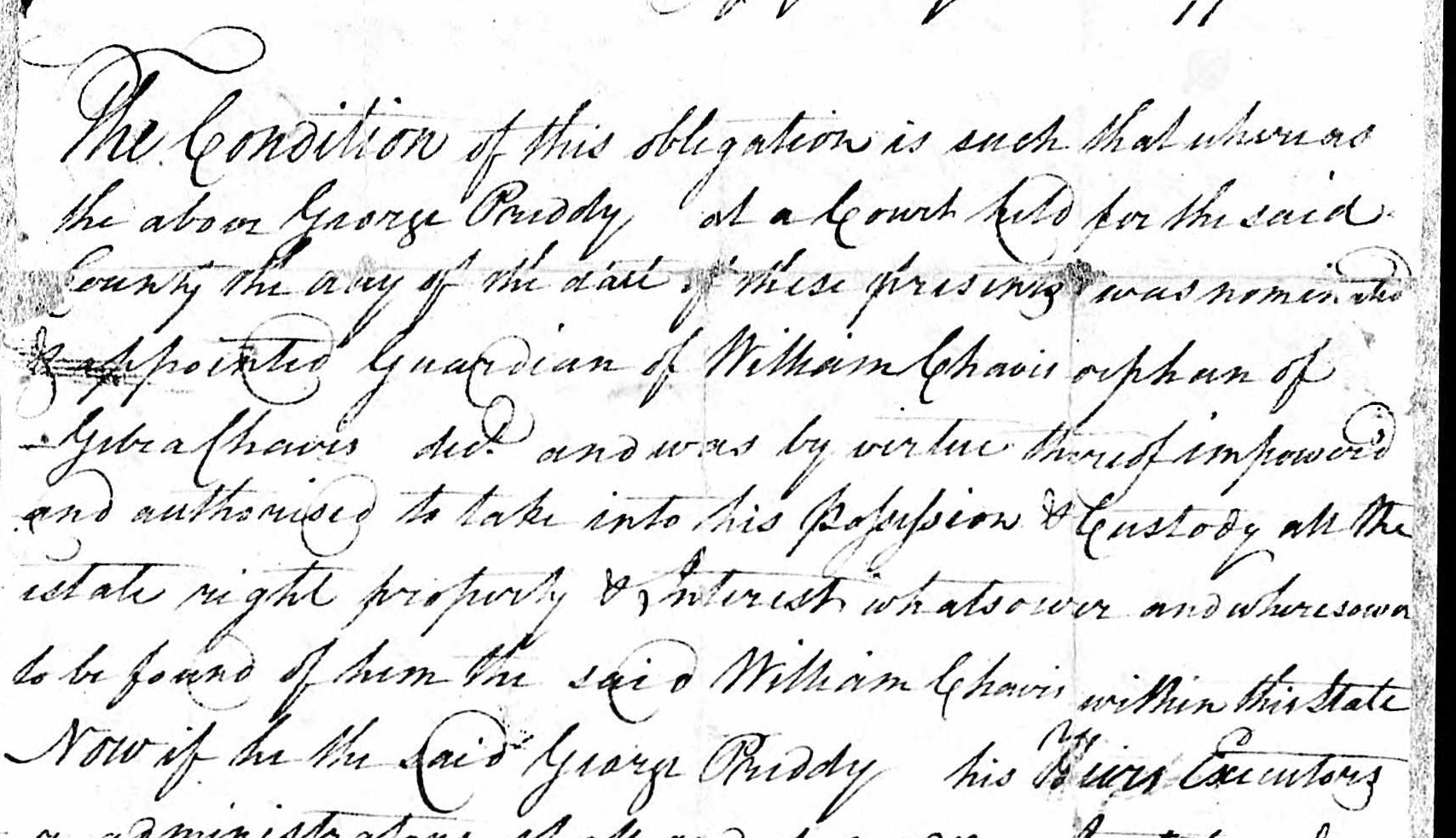

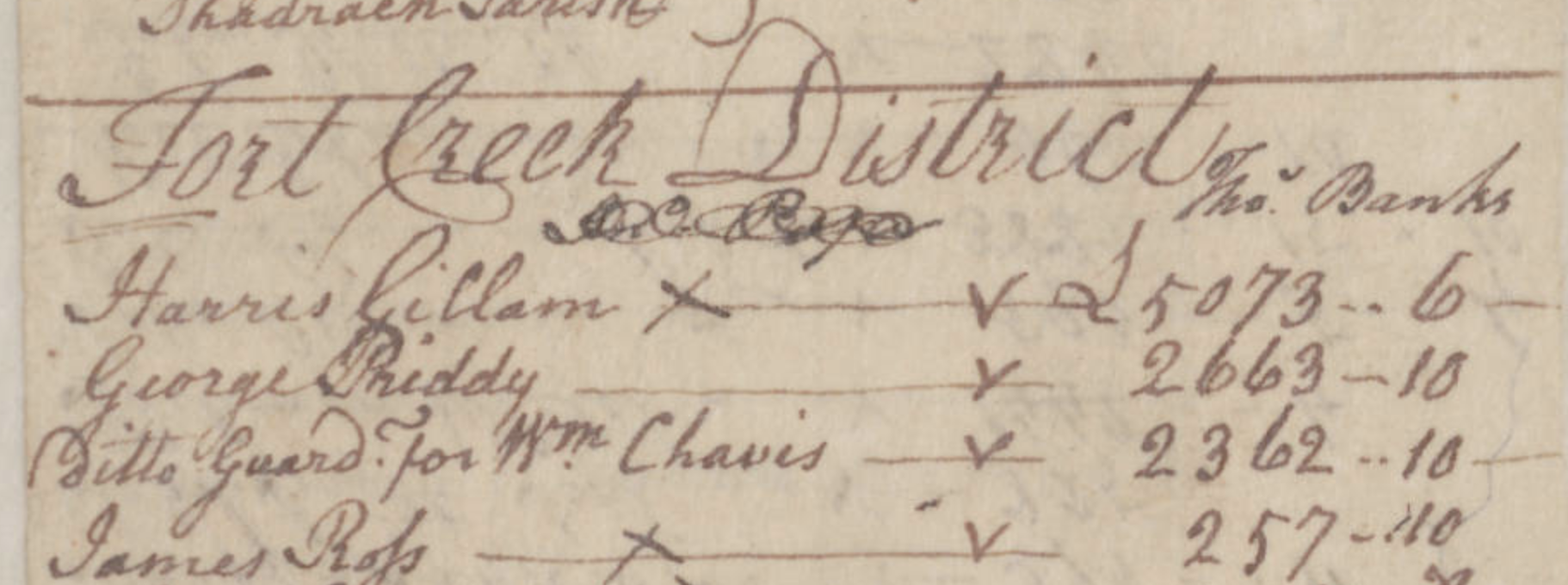

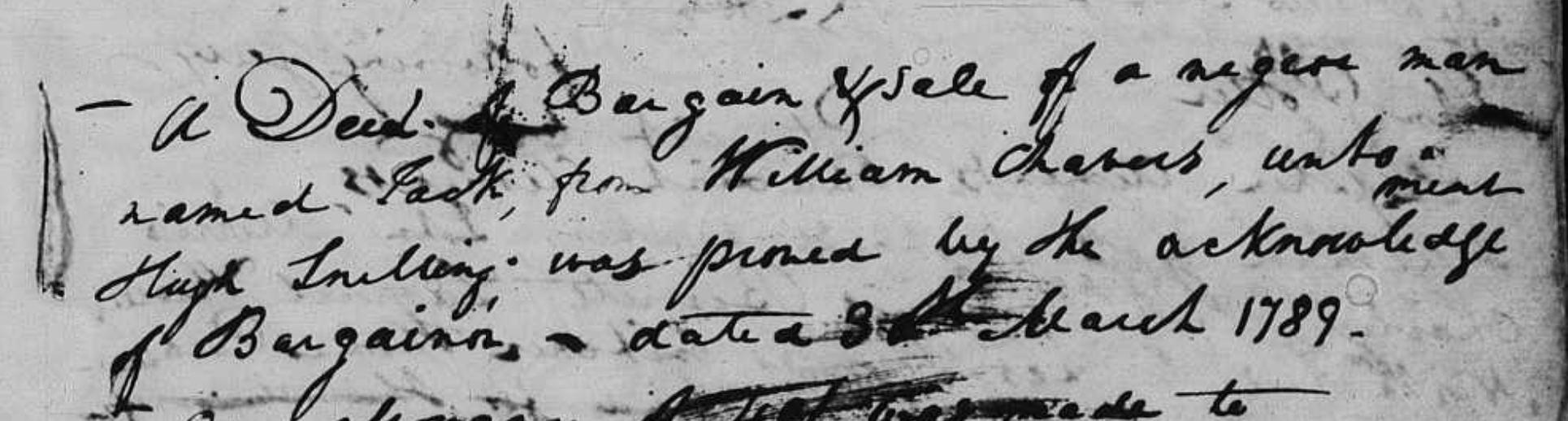

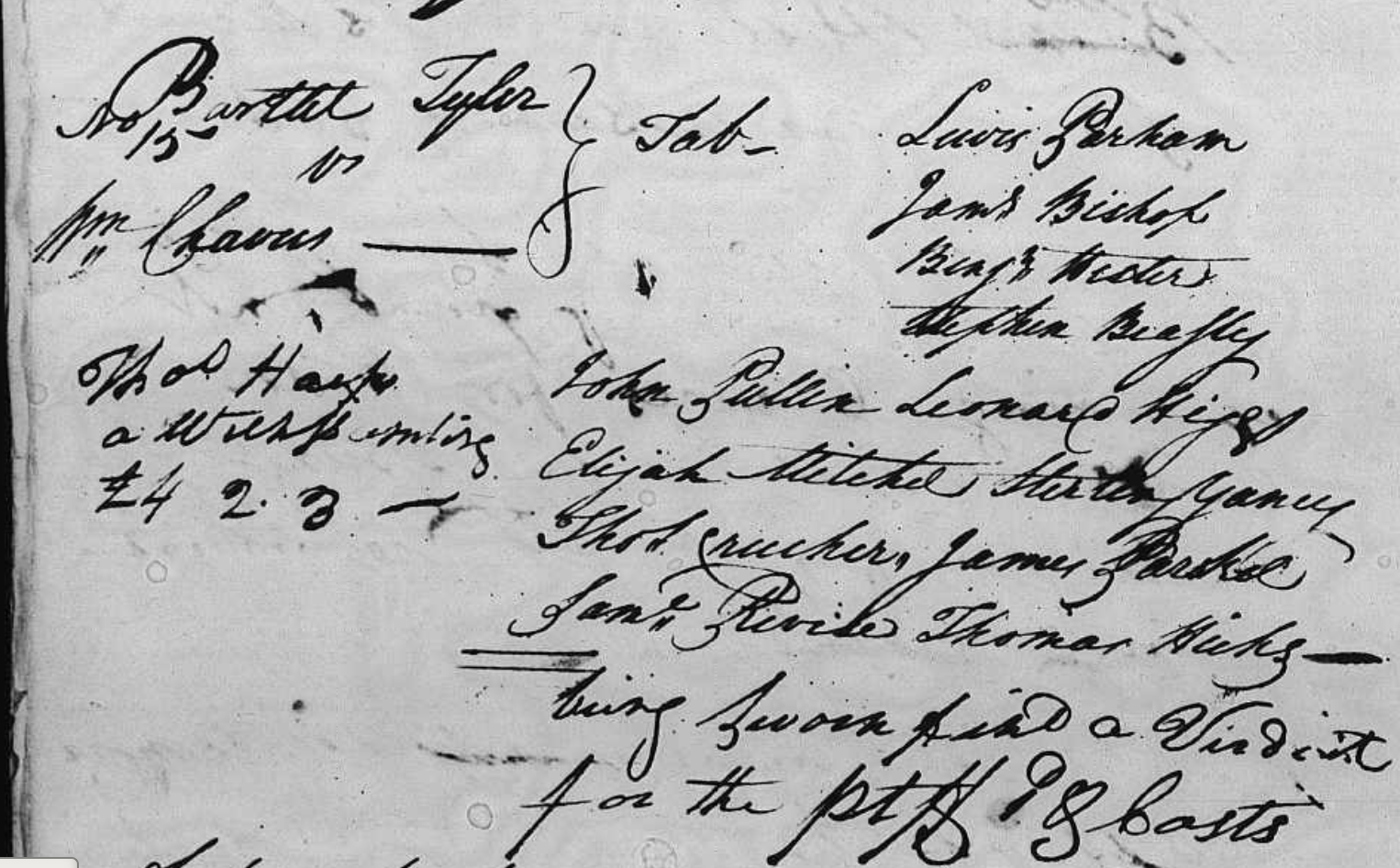

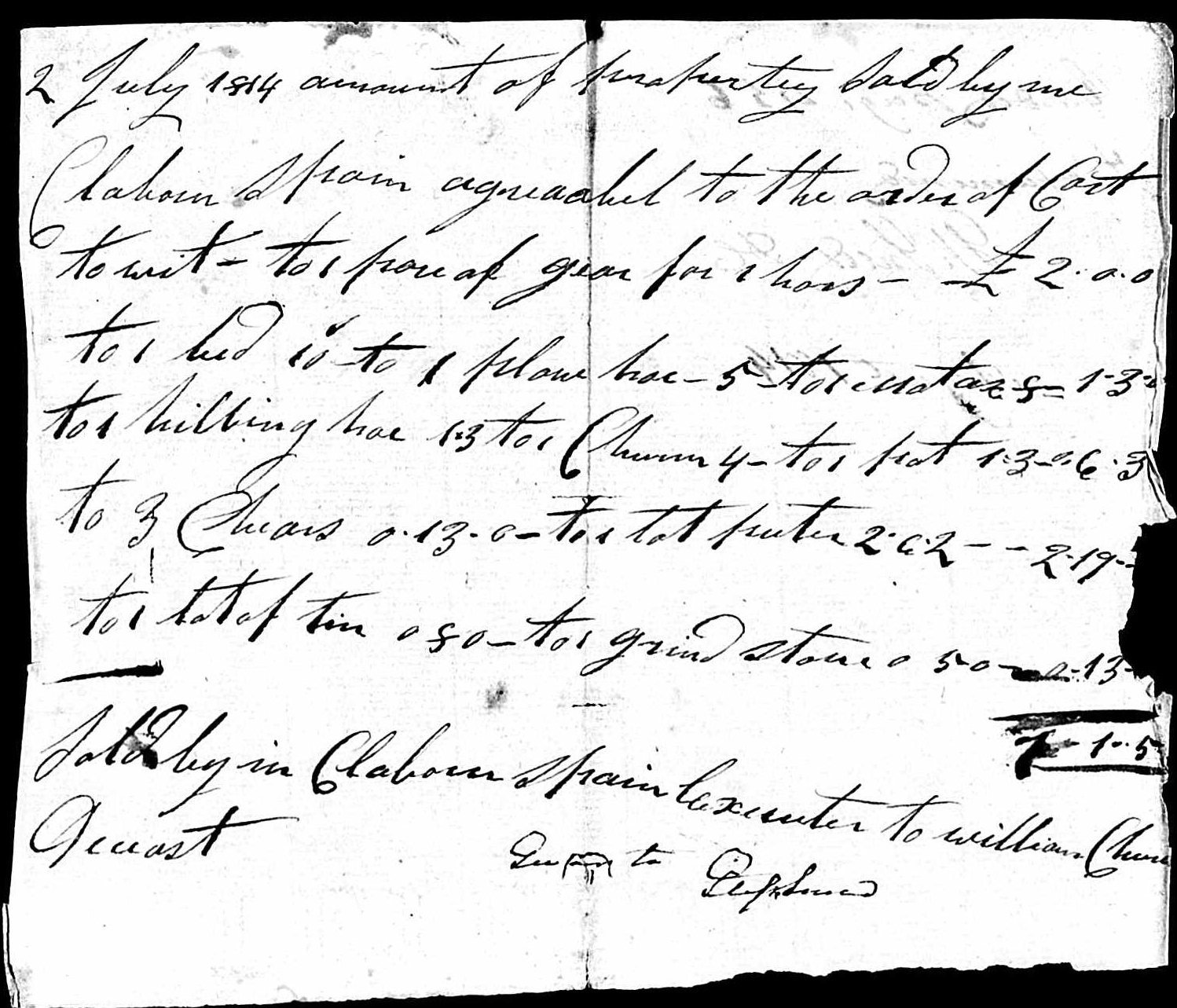

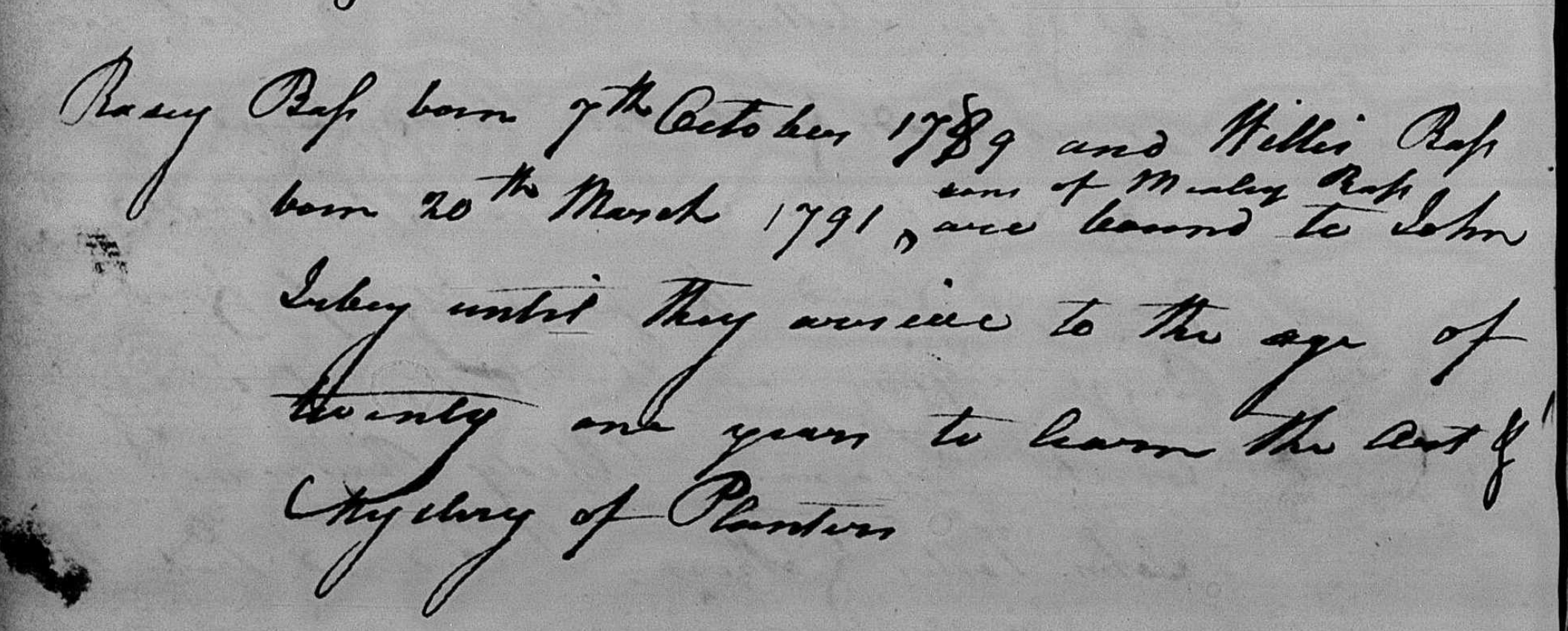

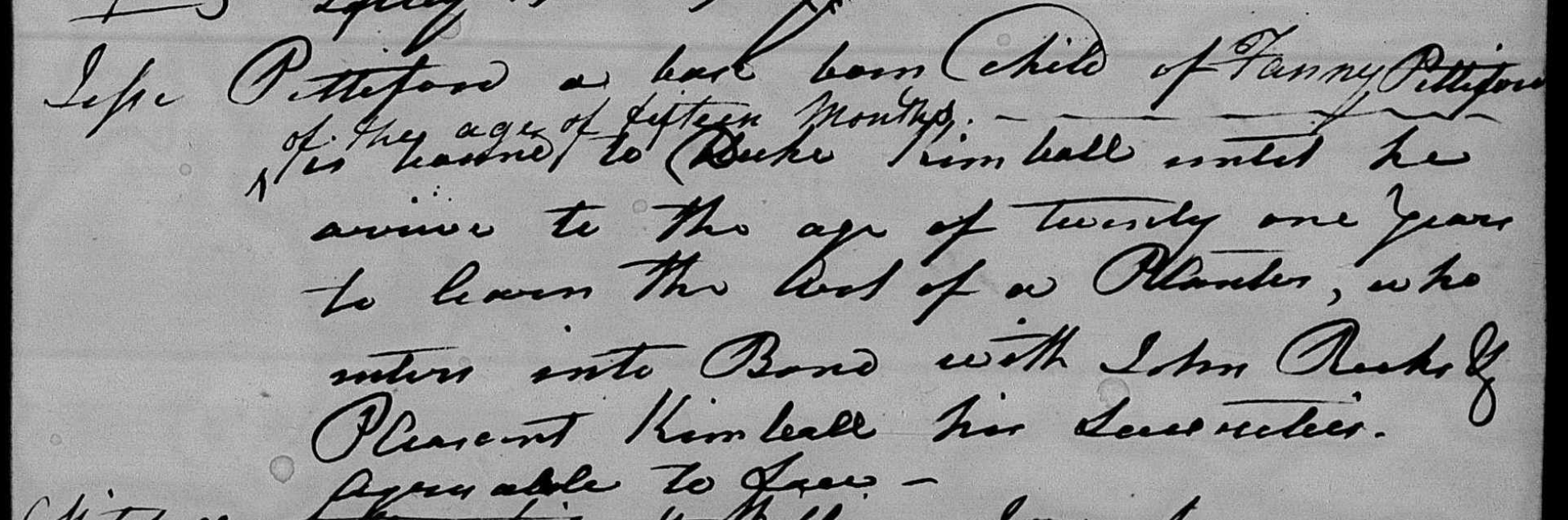

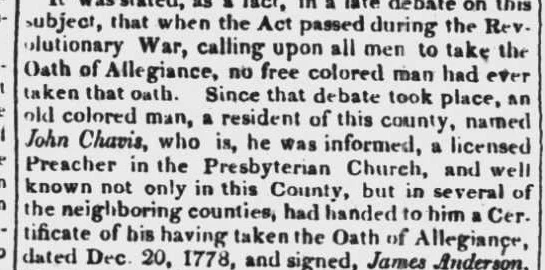

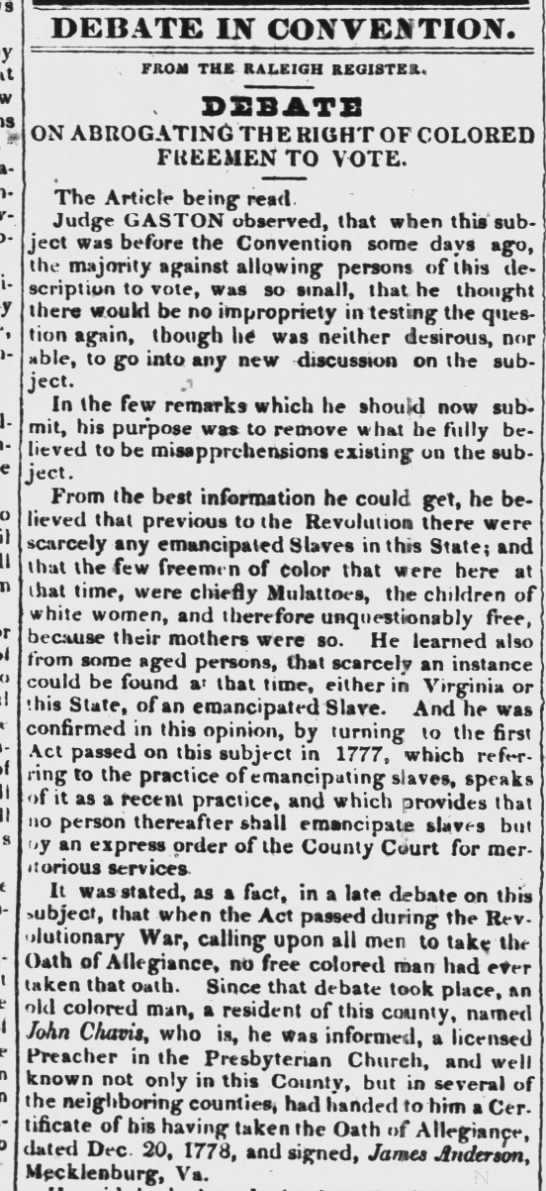

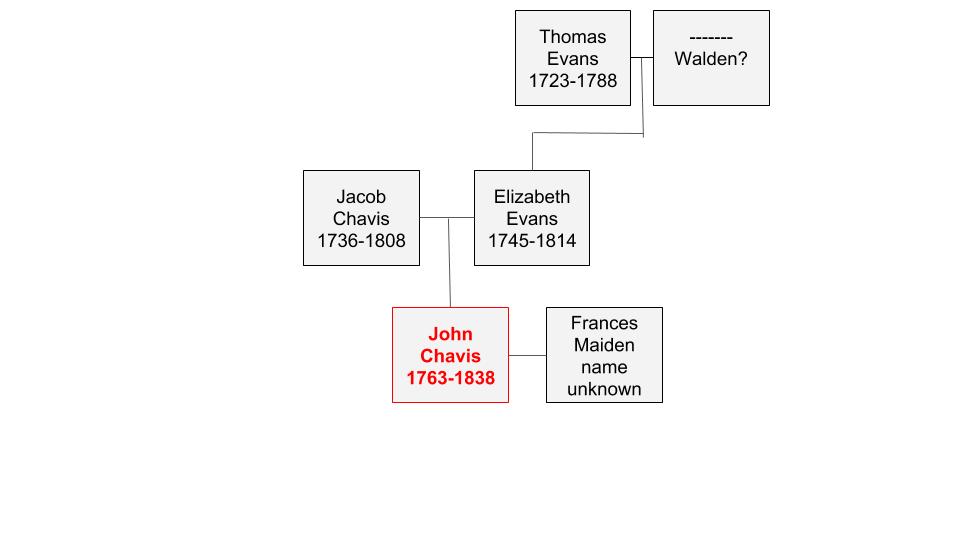

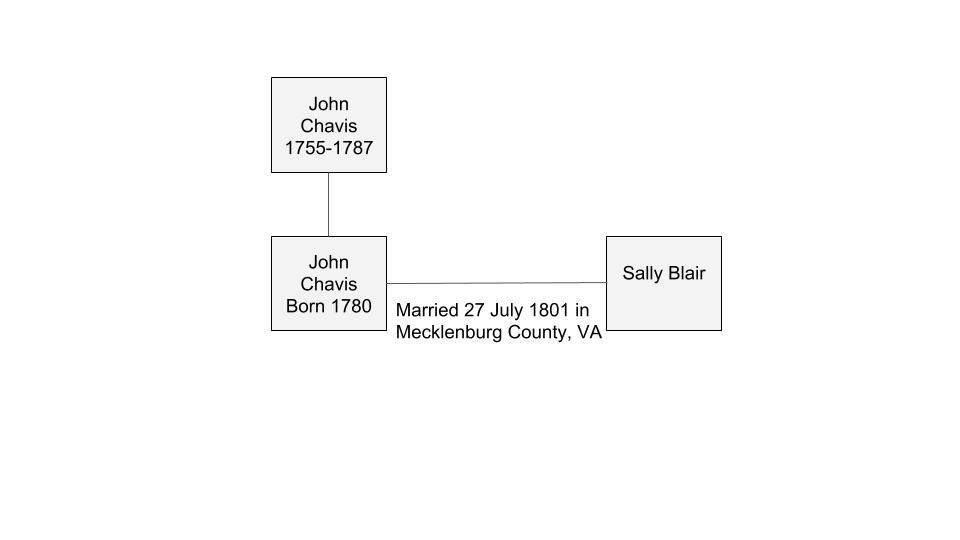

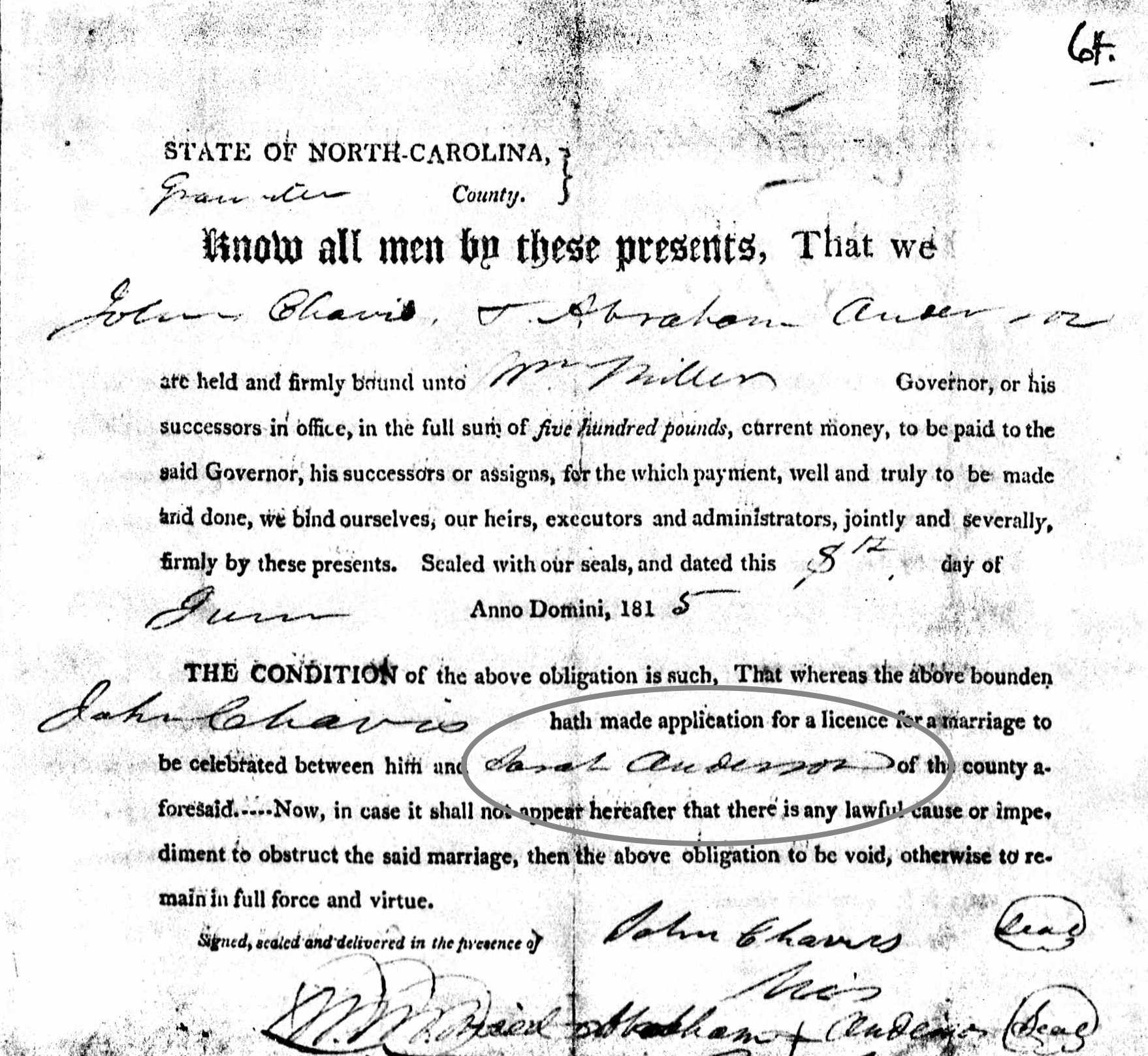

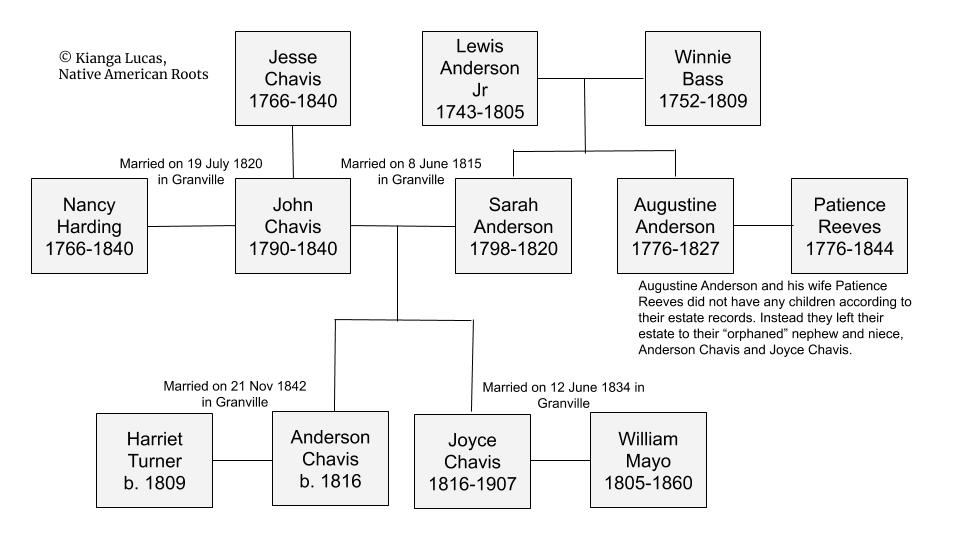

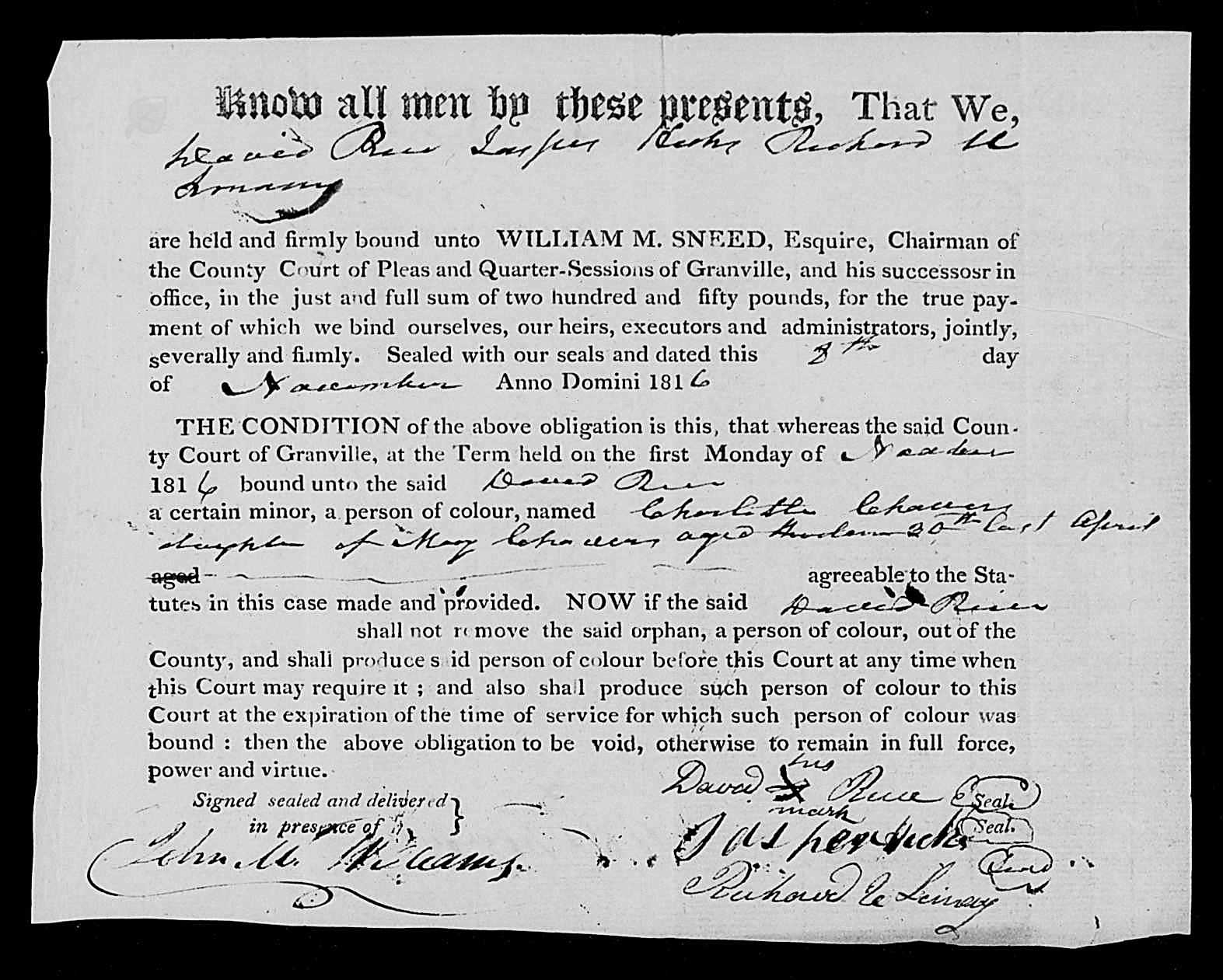

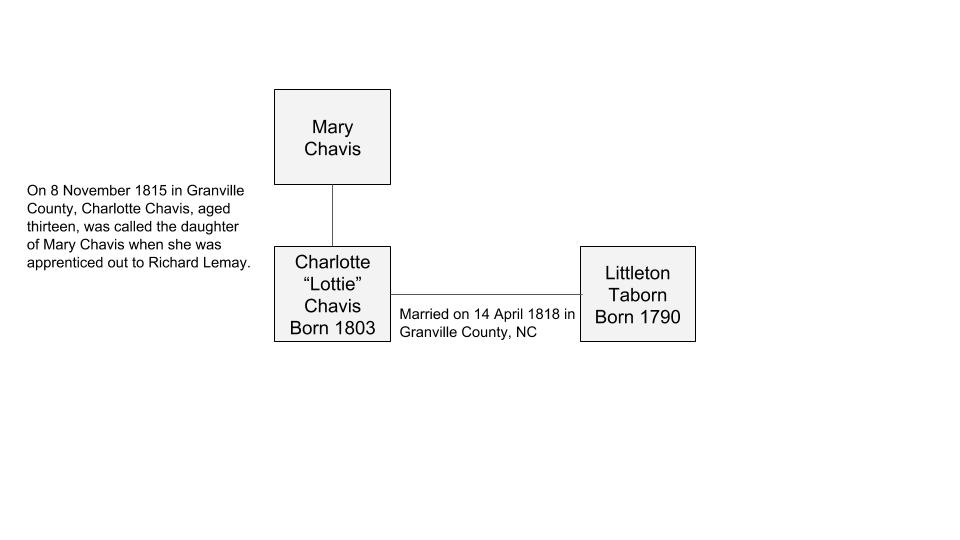

On 8 June 1815 in Granville Co, NC, John Chavis married Sarah Anderson with Abraham Anderson as the bondsman. This marriage record is for John Chavis (1790-before 1840) who was the son of Jesse Chavis (1766-1840) of Granville County. You can read more about Jesse Chavis’ family and ancestors

On 8 June 1815 in Granville Co, NC, John Chavis married Sarah Anderson with Abraham Anderson as the bondsman. This marriage record is for John Chavis (1790-before 1840) who was the son of Jesse Chavis (1766-1840) of Granville County. You can read more about Jesse Chavis’ family and ancestors

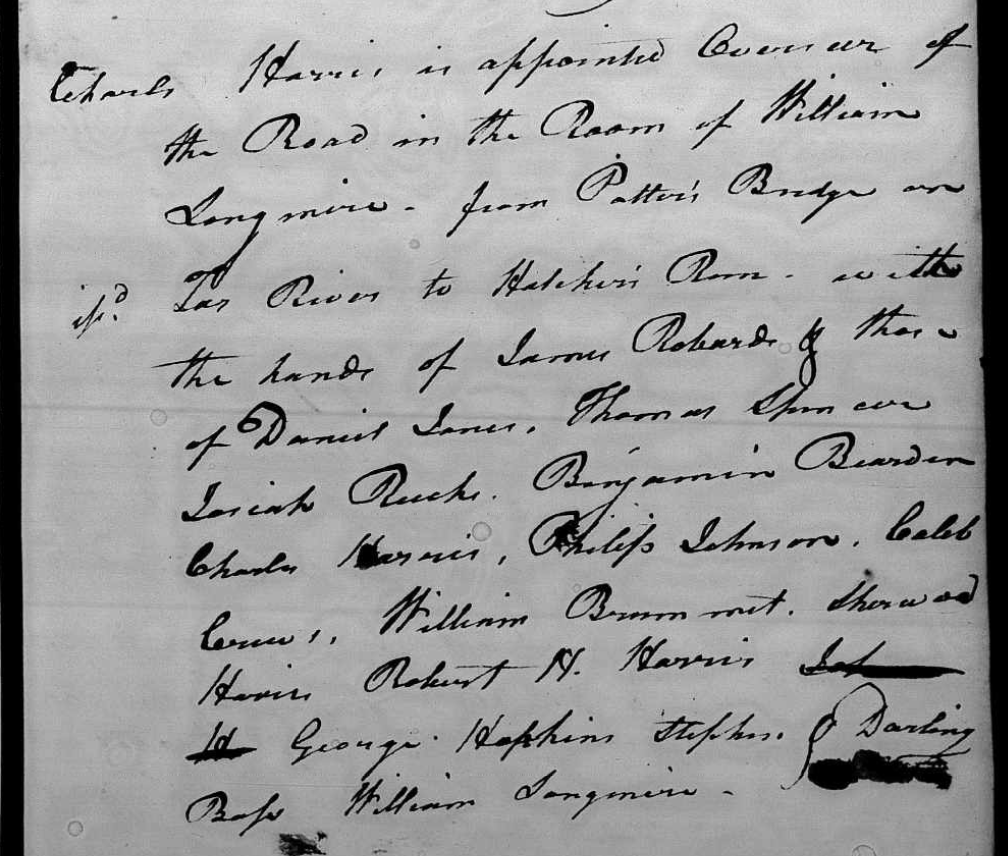

Revolutionary War Records

Revolutionary War Records