One of Granville County’s most infamous residents was a member of the Native American community named Archibald “Baldy” Kersey (1821-1899). Baldy showed little regard for the law, as he headed a gang of counterfeiters and thieves who traded stolen goods. Not even a jail cell could prevent Baldy from his life of crime as he would find inventive ways to break out. He also showed little regard for the racially segregated laws of the South. Baldy’s gang was interracial and Baldy had a known relationship with a white woman named Rovella Tanner with whom he fathered numerous children with. However to simply characterize Baldy as a “bad guy” does disservice to the complexity of his life. Baldy had a deep love and loyalty for family as demonstrated by “adopting” the fatherless children of his relatives. He also fought hard to the very end to keep possession of his family’s original land which actually resulted in a major United States Supreme Court decision on the constitutionality of North Carolina’s Homestead law. In this blog post, I will document the life of one of the community’s most colorful characters with the help of digitized court records and newspaper articles.

Baldy Kersey’s Lineages and Early Life

Archibald “Baldy” Kersey (1821-1899) was born in Granville County to Benjamin and Sally Kersey. Some family oral history indicates that Sally’s maiden name was Oxendine but I have not been able to locate a marriage record or any record that identifies her maiden name. Through his father Benjamin Kersey, Baldy descends from the Kersey, Evans, and Walden families. Baldy’s paternal grandmother Polly Evans (1765-1840) was sisters to my 5th great-grandmother Margaret Evans (b. 1753). I previously blogged about the Weyanoke and Nottoway/Tuscarora tribal origins of the Kersey family here and the Evans family here. “Kersey” is the standardized and most common spelling of the surname but throughout the documents in this blog post you will see the surname spelled in a variety of ways: “Kearsey” and “Kearzey”.

Baldy had numerous siblings who all lived within and married within the community:

Emily Kersey (b. 1820) married Samuel Richardson

Susan Kersey (b. 1825) married Samuel Johnson

Sally Kersey (1828-1911) married William Tyler Jr. (Baldy’ first wife Francis Tyler was sisters to William Tyler Jr)

Sophia Kersey (1829-1918) married William Anderson

Benjamin Kersey (b. 1831) never married and died young

Baldy Kersey first married Francis Tyler b. 1824 (daughter of William Tyler Sr and Martha Patsy Day) on 11 March 1841. Though they are listed together as a married couple in the 1850 and 1860 censuses, Baldy and Francis did not have any children together. However during their marriage, Baldy did father a child named Mary Jane Chavis (1857-1929) out of wedlock with a woman named Lula Chavis.

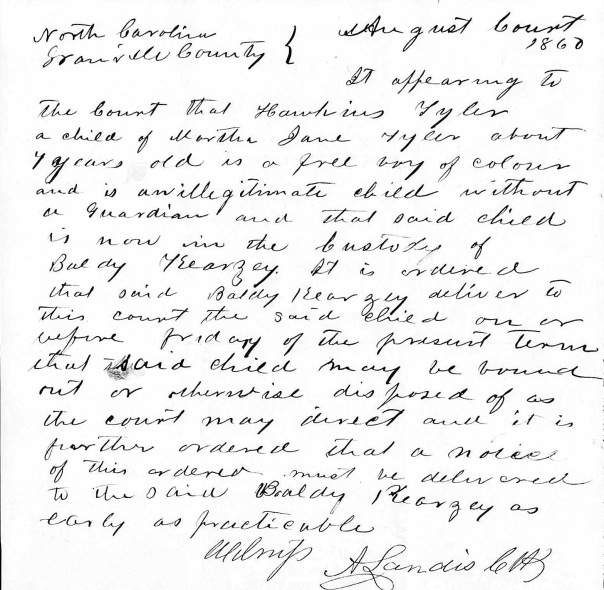

Also during his first marriage, Baldy adopted the 4 “illegitimate” children of his wife’s sister Martha Jane Tyler (b. 1830). The four children were: Francis Tyler b. 1850, Elizabeth “Betsy Ann” Tyler b. 1851, Hawkins Tyler (1854-1921), and Amanda Tyler (1858-1955). From that point forward, the siblings interchangeably used the Tyler and Kersey surnames and were commonly known as Baldy Kersey’s children.

Later Baldy Kersey had a relationship with a white woman named Rovella Tanner but could not legally marry her because of laws forbidding interracial marriages. They had numerous children together which I discussed in detail in this blog post.

Baldy Kersey’s Gang

In her book, “Unruly Woman, The Politics of Social and Sexual Control in the Old South”, historian Victoria Bynum includes a brief discussion on the illegal activities of Baldy Kersey. During the Civil War, Baldy Kersey was the leader of an interracial gang of people who traded looted goods. It was a very extensive underground network that went from Granville County all the way to the Atlantic Coast. This network included “free people of color”, as well as white men who had deserted the Confederate Army and black slaves.

The Civil War brought about great poverty in the South and poor people especially had a hard time finding goods. Baldy Kersey’s gang filled this void by providing a way for poor people to be able to acquire goods. But it was not just the illegal activities that worried authorities, it was the interracial nature of Baldy’s gang that was a direct slap to the face of the racially segregated South. Granville Co Sheriff William Philpott explained to North Carolina Governor Vance that Baldy was:

the worst rogue and seducer of slaves I have ever known. He has a range from here to the extremity of the state east, as he has been trading that way for years.

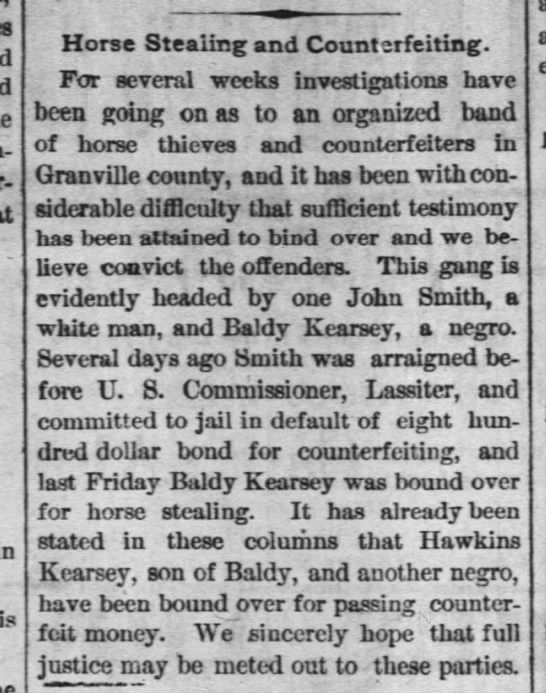

In a later newspaper article from 16 Mar 1880, we see that Baldy Kersey and a white man named John Smith were the leaders of a gang that dealt in counterfeit money and horse stealing. We can also see that counterfeiting and stealing was a family affair for Baldy, as his “adopted” son Hawkins (Tyler) Kersey was also a member of the gang:

The more I have learned about Baldy Kersey, the more he reminds me of another contemporary from his time: Henry Berry Lowry. Lowry is the famed ancestor of the Lumbee and Tuscarora of Robeson Co. In fact, Baldy Kersey and Henry Berry Lowry were cousins. Lowry’s paternal grandmother was Sally Kersey who was described as a “half breed Tuscarora Indian”. Like Kersey, Henry Berry Lowry lead an interracial gang of thieves who refused to enlist with the Confederacy during the Civil War. I’m sure the two men crossed paths during their extensive networks throughout the state. And according to Baldy Kersey’s great grand nephew Robert Tyler, the family has always known that they were cousins with Henry Berry Lowry.

In the following sections, I’m going to explore in detail some of Baldy Kersey’s major court cases.

John Crabtree V. Baldy Kersey and the Stolen Wagon Hubs

The earliest court case that I could find where Baldy Kersey was charged with larceny was from an accusation in 1863. It is worthwhile to note that Baldy was already approximately 42 years of age in that year, so it seems unlikely this was his first offense. Familysearch recently digitized a collection called, “North Carolina, State Supreme Files, 1800-1909” and I was able to find a number of cases from our community. One such case was State V. Kearzey 61 N.C. 481 (N.C. 1868). This was an appeals decision from an earlier case that was in the Granville County District Court and North Carolina Superior Court. Both lower courts had previously ruled in favor of the state in the 1863 larceny case. So within this North Carolina State Supreme Court appeal are the transcripts from the the previous courts’ rulings of the 1863 case which provide lots of detail as to what exactly Baldy Kersey was accused of. You can access the entirety of the files for this case here (these are in original handwriting and not transcribed).

The details of the case are quite interesting because they demonstrate the tenacity of Baldy Kersey. On 5 March 1863, John Crabtree came before the court and testified that Baldy Kersey had committed larceny and as a result Kersey was indicted for larceny in May 1863. Crabtree was a wagon maker who had a shop in Oxford. A year earlier in February 1862, Crabtree met a man named Murray (first name not given) who was also a wagon maker who had a shop about 10-12 miles outside of Oxford. Murray was preparing to leave the state and needed to sell his wagon making materials. Crabtree agreed to purchase the materials which included distinctive wagon hubs made from walnut timber.

Because the two shops were 10-12 miles apart, the purchased materials needed to be transferred and this is where Baldy Kersey enters the story. In the spring of 1862, Crabtree was in the process of transferring the goods when he saw Baldy Kersey just outside of Murray’s shop and asked him to assist in transferring the materials to his own shop in Oxford. Crabtree even told Kersey where the key was to his shop so that Kersey could let himself in to unload the goods. (Not to excuse Kersey’s actions but if Kersey was a known thief, why would Crabtree enlist his help?)

Baldy Kersey apparently picked up the materials but never transferred them to the shop. Instead he brought the materials home. Crabtree never realized that Kersey did not transfer the goods to his shop because it appears Crabtree never had a full list of the items he purchased from Murray. Fast forward a year later to March 1863, and Crabtree reported that several individuals were going through Baldy’s house looking for other stolen goods. Crabtree was not the only person who had been wronged by Baldy. While going through his house, these individuals found the wagon hubs that Crabtree purchased from Murray a year earlier. There was little doubt that these were the same wagon hubs because they were made from walnut and had the same distinctive marks. Kersey was present during the search and denied that the wagon hubs belonged to Crabtree and instead insisted he purchased them from a man named Grissom who left the county several years earlier.

Indicted on larceny charges by the grand jury in May 1863, Baldy Kersey decided to leave the county and hide out instead of coming to court and answering the charges against him. In the court records we see that starting in August 1863, Baldy Kersey could not be located. Every two months, the courts would call the case up but it had to be delayed on account of Baldy Kersey being on the run. This continued on until May 1866 when Baldy Kersey finally showed up to court to answer for the charges against him.

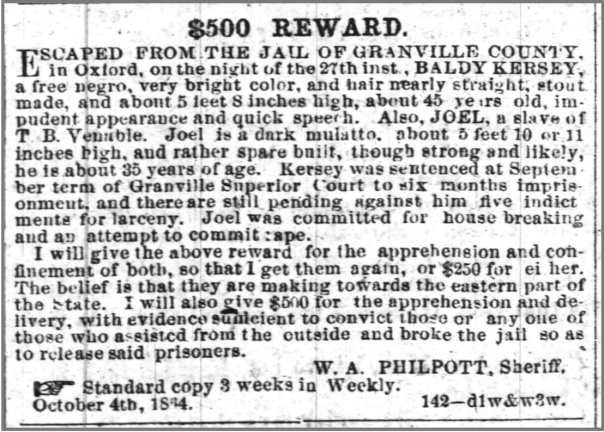

During Baldy Kersey’s 3 years on the run, the documentation gets a bit confusing and conflicting. According to the court documents for this larceny case involving Crabtree, Baldy was consistently on the run from August 1863 through May 1866. But it appears that Baldy was picked up by the sheriff at some point and started to serve a 6 month jail sentence on yet another larceny charge. We know this because on 27 October 1864, we see a notice in the newspaper alerting the public that Baldy Kersey had escaped from jail:

We learn from this notice that Baldy Kersey had been sentenced in September 1864 to 6 months of imprisonment for larceny. The notice doesn’t specify the details of this conviction but it does say that there were still 5 outstanding larceny indictments against him. We know one of those five indictments was the theft of Crabtree’s wagon hubs.

To escape from jail is a big deal. According to later witness testimony, Baldy used bribery and the assistance of two white men to escape from jail.

When Baldey Kersey returned to court in May 1866 after 3 years on the run, he entered a plea of “not guilty” and a trial date was set for August 1866. However Baldy was able to convince the court that he was not ready for trial and asked for a delay which was granted for November 1866. And not just one delay, he was able to delay the trial multiple times so that the trial did not take place until May 1867.

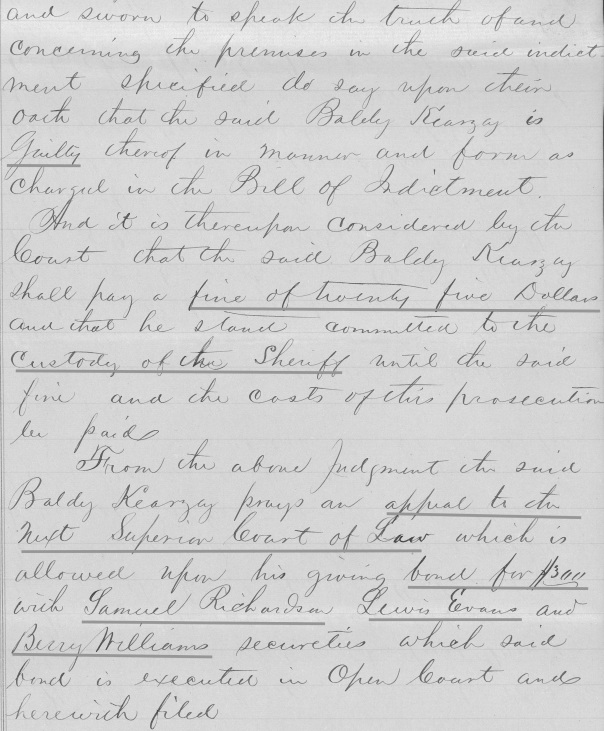

For the trial, Kersey hired a defense attorney to argue his side of the case. However a jury found him guilty of larceny. Kersey’s attorney asked for a new trial which was denied. The defense attorney also asked the judge to squash the punishment citing other statues that petty larceny under $25 was not punishable by a criminal court. However the court overruled the defense attorney’s motion.

As a result of the “guilty” judgment, Baldy Kersey was ordered to pay a fine of $25. He was further ordered to be held in the custody of the sheriff until the fine and court costs were paid off. Baldy Kersey appealed the decision and formally asked for his case to be reviewed by the North Carolina Superior Court which was granted. He had to post a bond for $300 and Samuel Richardson, Lewis Evans, and Berry Williams were his sureties. All three men were from the Native community and Samuel Richardson was Baldy’s brother-in-law.

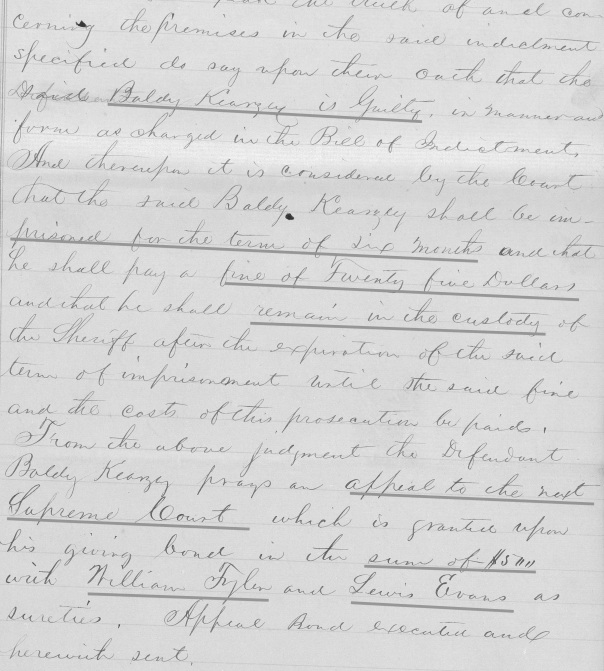

In the fall 1867 term of the North Carolina Superior Court, the jury found Baldy Kersey “guilty” again of stealing Crabtree’s wagon hubs. He was ordered to be held 6 months in jail and to pay a fine of $25. He was further ordered to be held in jail until the court costs were paid off. So this time Baldy Kersey appealed the decision to the North Carolina Supreme Court which was granted. He was ordered to post a bond for $500 and this time William Tyler and Lewis Evans were his sureties. Lewis Evans was the same Lewis Evans from the previous $300 bond and William Tyler was also from the community and Baldy Kersey’s brother-in-law.

The North Carolina Supreme Court reviewed the case in the January 1868 term and you can read the court’s transcribed decision here. By citing earlier precedents, Judge Reade found that there was no error in the lower court’s judgments and upheld the ruling. The court ordered that Baldy Kersey and his sureties Lewis Evans and William Tyler pay $17.95 – the amount of the court costs. However on 16 March 1868, a Congressional special order declared that Baldy Kersey and his sureties did not have to pay the judgment and in fact annulled the judgement entirely. All judgments made by any North Carolina court on this larceny case after the date of 29 April 1865 were annulled. This was likely a result of the Reconstruction laws after the Civil War. All of the court judgments against Baldy for this larceny case happened after that date, so Baldy was excused for paying the judgment or going to jail. However if the court wanted to indict him on new charges relating to theft of the wagon hubs, they could do so and start the process over again.

Baldy Kersey V. Avery Taborn, and Horse Thievery

Baldy Kersey was the defendant in yet another case of larceny involving a stolen horse that he “sold” to Avery Taborn. This is another interesting case because the details included in the records speak volumes about Baldy’s character. The records for this larceny case are actually found within the Freedmen’s Commission records and not the court records. After the Civil War, the U.S. formed the Freedmen’s Bureau to assist freed slaves with efforts in rebuilding their lives. Both Baldy Kersey and Avery Taborn were “free people of color” from the Native American community in Granville, but the Freedmen’s Bureau serviced them as well. On Familysearch, you can access these records in the folder “North Carolina, Freedmen’s Bureau Assistant Commissioner Records, 1862-1870.”

You can read the entirety of Baldy Kersey’s case here (a lengthy case with pages in original handwriting). We learn that in August 1868, Baldy Kersey sought out the Freedmen’s Bureau to hold a hearing about an earlier trial, Taborn vs. Kersey, in which Baldy felt the judgment against him was not lawful. A Freedmen’s Bureau agent named E.T. Lamberton took up the case and from his notes, we learn more about what happened.

In 1866, Baldy Kersey stole a horse from the Draughan family in Edgecombe County, NC. He returned to Granville County and traded the stolen horse for a mule owned by Avery Taborn that was worth about $150. Avery Taborn b. 1832 was the son of Littleton Taborn and Charlotte Chavis, who were a prominent family in the Native American community. As you will recall from earlier, Baldy Kersey lead an underground network of traded stolen goods. A few days later when Taborn rode the stolen horse into Oxford, the Draughan family saw Taborn and questioned him about the horse where it was revealed that Baldy Kersey had stolen the horse. Baldy was subsequently arrested by Granville Co Sheriff William Philpott and indicted on larceny charges. We learn that Baldy had the case moved from Granville County court to Franklin County court because he felt he could not get a fair trial in Granville. However there was a technical error with transferring the transcripts to Franklin, so the the case was dismissed. The court did order for the Draughan family to retrieve their stolen horse from Avery Taborn, but now Taborn was out $150 for the loss of the mule because Baldy had already sold it off.

Avery Taborn tracked down a Captain Evans of the Freedmen’s Bureau to seek compensation for his property loss. Capt Evans was able to negotiate a deal in which Baldy was to give one of his own horses and $75 to Taborn to make up for the loss. Baldy did deliver a horse to Taborn but a short while later stole it back from Taborn and sold it to his son-in-law Benjamin Richardson. Benjamin Richardson (b. 1844) was the husband of Baldy Kersey’s “adopted” daughter Francis Tyler. Baldy admitted to taking the horse back from Taborn but did not agree that it constituted theft because he felt that Captain Evans’ ruling was unlawful. Because Baldy had never been convicted of that larceny charge, there was some truth to his protests.

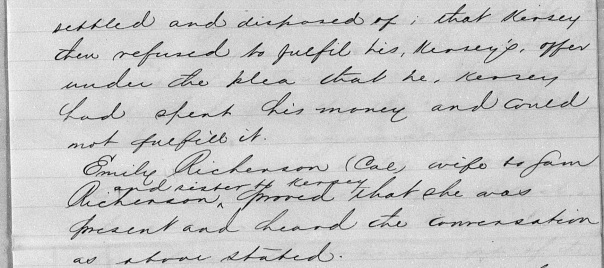

There was another attempt to make Taborn financially whole again. Kersey went to Taborn and in front of several witnesses agreed to pay Taborn $100 plus 300 lbs of meat for 30 cents a pound. A few days later when Taborn agreed to the deal, Kersey reneged and said he already spent the money.

So what does Baldy have to say about all of this? Well, he admitted under oath that he paid Capt Evans $50 to bribe him into ruling in his favor. But despite receiving the money, Capt Evans still ruled in Taborn’s favor and that is why Kersey felt the judgment was unfair. Bribery is also how Baldy was able to escape from jail in 1864, so clearly we see a pattern here where Baldy believes he can pay people off in order to escape punishment.

In the notes from Lamberton, we see that Baldy was quite eager for the Freedmen’s Bureau to look into this case and rule in his favor because of the threat of having to sell his own property to pay Taborn. Clearly, Kersey’s thievery was starting to catch up to him financially. The agent ordered for both parties to gather witnesses and hire legal counsel. Due to his reputation for not paying people, no attorney agreed to represent Baldy in the hearing. On the other hand Avery Taborn hired a white attorney Col. Leonidas C. Edwards to represent him in the hearing. Col. Edwards is a name to not forget because he was the plaintiff in the biggest legal case involving Baldy Kersey that will be discussed in the next section.

Agent Lamberton’s notes shows that he had sympathy for Kersey not being able to hire an attorney, but he could not delay the trial any longer because the witnesses were being inconvenienced. Both Taborn and Kersey brought witnesses to testify but according to Lamberton, Baldy’s own witnesses seemed to side with the plaintiff. In fact Baldy’s sister Emily (Kersey) Richardson and brother-in-law Samuel Richardson provided testimony that supported Taborn.

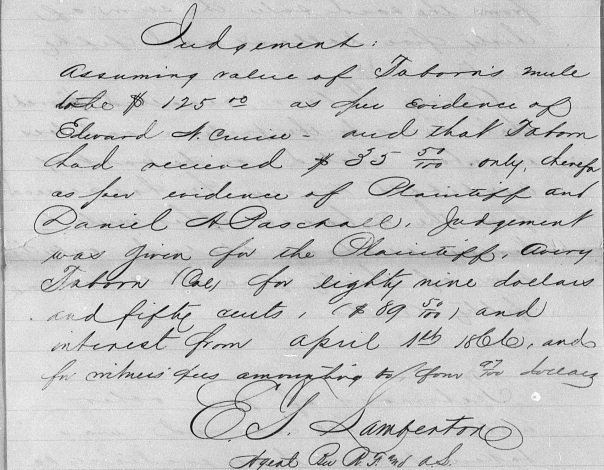

Lamberton also noted that Baldy did not offer any substantive arguments in his favor, so it was a one sided hearing. Lamberton ruled in Taborn’s favor and ordered that Kersey pay him $89.50. From witness testimony the mule was valued at $125 and Taborn had already been paid $35.50 from the sale of another one of Baldy’s horses. So that left a remaining balance of $89.50. In addition, Baldy was ordered to pay interest on the amount from 1866 to present as well as a fee of $4.97 for securing witnesses to testify.

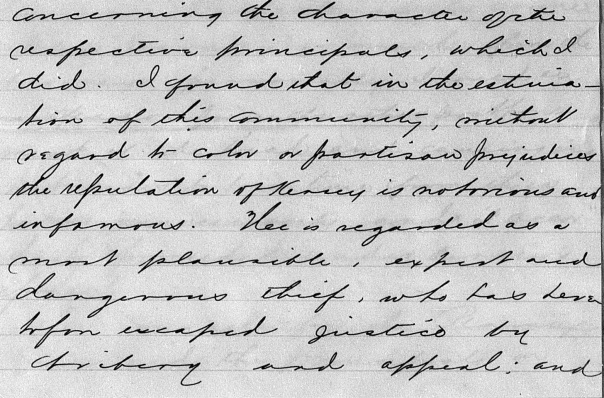

What is very telling is that at the end of his notes, Lamberton adds in some additional observations about the character of Baldy Kersey. He says before the hearing, he never knew of Baldy but during the hearing he learned a lot about him. Lamberton explains that the community regarded Kersey as:

“notorious and infamous….he is regarded as a most plausible, expert and dangerous thief, who… escaped justice by bribery and appeal”.

Col. Leonidas C. Edwards V. Baldy Kersey and North Carolina’s Homestead Law

The last legal case that I will discuss went all the way up to the United States Supreme Court. Edwards V. Kearzey 96 U.S. 595 (1877) has been cited 237 times since its ruling and was cited as recently as 2014. It’s quite an important case involving contract laws and the constitutionality of Homestead laws. But let’s first discuss the beginnings of this important court decision.

The Granville County court had ordered several judgments against Baldy Kersey for larceny. Plaintiffs in these cases that were ordered to receive compensation from Baldy Kersey included: B.L. and D.A. Hunt, Avery Taborn, and William Philpott. Though these judgments came in 1868 and 1869, they resulted from unpaid contracts from several years earlier (this detail is important). As a result of these outstanding judgments that had not been paid by Baldy Kersey, on 18 January 1869 a lien was put against his property.

Let’s take a moment to discuss Baldy’s property. It was 173 acres of land located in Fishing Creek township in the heart of the Native American community founded by William Chavis in the mid 1700s. Adjoining property owners included William Tyler Sr. and Manson Stewart. This land was on the waters of what is called “Hatcher’s Run” (the documented Native American Hatcher family including David Hatcher, described as “half Indian” in his Revolutionary War records are the namesake for this waterway) and had been passed down in Baldy’s family from earlier generations. It was very important for Baldy Kersey to hold onto this land. In addition, it was the only land he owned, so if he lost it, he would be homeless. With young children to raise, there was no way he could risk that. Therefore on 22 January 1869, Baldy Kersey applied to have his land transferred to a homestead.

In 1868, North Carolina enacted a new state constitution that took affect on 24 April 1868. Sections 1 and 2 of Article 10 in the Constitution state that every homestead that was valued at $1,000 or less was exempt from being sold to pay off debt. Baldy’s property fit the criteria so he applied for a homestead. Despite his application, Sheriff William Philpott sold the entirety of Baldy Kersey’s 173 acres of land on 5 March 1869 to Col. Leonidas C. Edwards for $150.

This is the same Col. Leonidas C. Edwards who was the attorney hired by Avery Taborn when he sued Baldy Kersey for the loss of his mule. From what I can surmise, Col. Edwards was familiar with Baldy’s legal troubles and the upcoming sale of his land. He saw an opportunity to purchase prized land for a low price and followed through.

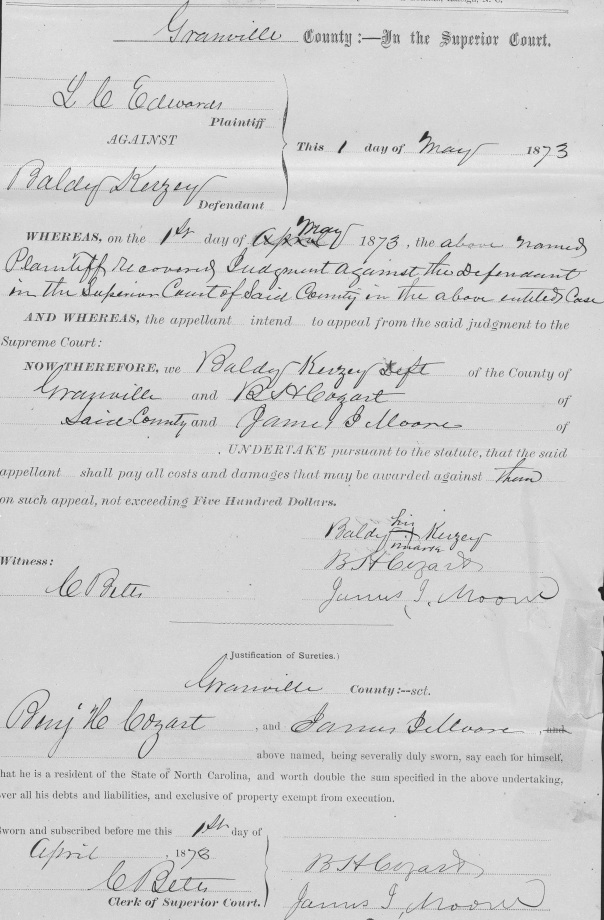

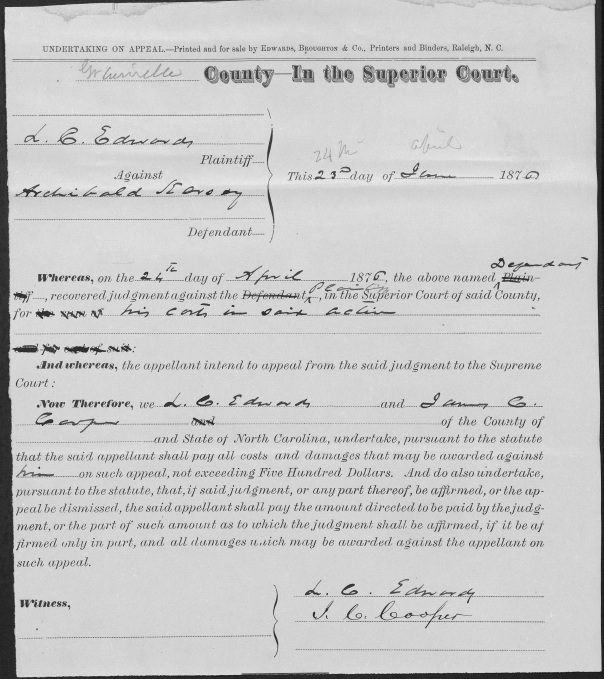

Unsurprisingly, Baldy Kersey protested the sale of his land and refused to turn it over to Col. Edwards. As a result, on 31 March 1869, Col. Edwards, plaintiff, filed suit against Baldy Kersey, defendant, in the Granville County Superior Court. The case was delayed for a number of years for unspecified reasons. And finally in the 1 May 1873, the Superior court ruled in Col. Edwards’s favor in large part because the judge excluded evidence which showed that Baldy filed an application for a homestead. Not only did the court rule that Col. Edwards should recover possession of the land, they ordered Baldy Kersey to pay a fine of $310 and 12.5 cents for punitive damages. As a result, Baldy posted a $500 bond to appeal the court’s decision to the North Carolina Supreme Court.

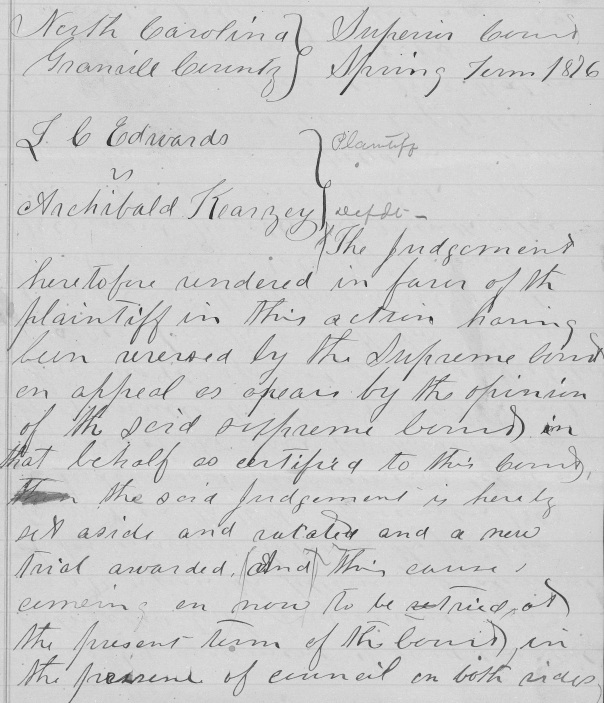

Edwards V. Kearsey, 74 N.C. 241 (N.C. 1876) is the North Carolina Supreme Court Case resulting from Baldy Kersey’s appeal. You can access the entirety of the case here which includes transcripts from the Superior Court case and ruling (the pages are in the original handwriting). The decision was handed down in January 1876 by Judge Bynum. Citing North Carolina’s Homestead law, Judge Bynum reversed the North Carolina Superior Court’s decision in favor of the plaintiff Col. Edwards. You can read a transcribed version of Judge Bynum’s ruling here. Specifically, Bynum notes that the original judgments against Kersey were docketed after the adoption of North Carolina’s 1868 Constitution, therefore the Homestead law was in affect. This was a big win for Baldy but the fight to keep his land was far from over.

Due to the North Carolina Supreme Court’s reversal, the Granville County Superior Court set aside its judgement against Kersey and ordered a new trial.

The facts of the case were argued once again with the plaintiff Col. Edwards insisting that the Homestead law did not protect Baldy’s land and the defense insisting the opposite. On 24 April 1876, the court issued a judgment in favor of defendant Baldy Kersey and agreed that the Homestead Law was in affect and applied to Baldy’s land. The judge ordered that the plaintiff was not entitled to the land and that Baldy recover court costs. Col. Edwards and his attorney filed to appeal the decision back to the North Carolina Supreme Court and posted a $500 bond.

Edwards V. Kearsey, 75 N.C. 409 (N.C. 1876) is the second North Carolina Supreme Court decision regarding this case. You can read the entirety of the case here which includes transcripts from the Superior Court’s decision (the pages are in the original handwriting). In June 1876, the Judge Reade issued a ruling affirming the Superior Court’s decision in favor of the defendant Baldy Kersey. You can read a transcribed version of Judge Reade’s decision here. Judge Reade agreed that the Homestead Law applied to Baldy’s land. This was a major victory for Baldy Kersey. Not just one, but two North Carolina Supreme Courts agreed that his land was protected and not subject to be sold off to pay debts.

But it was still not over…

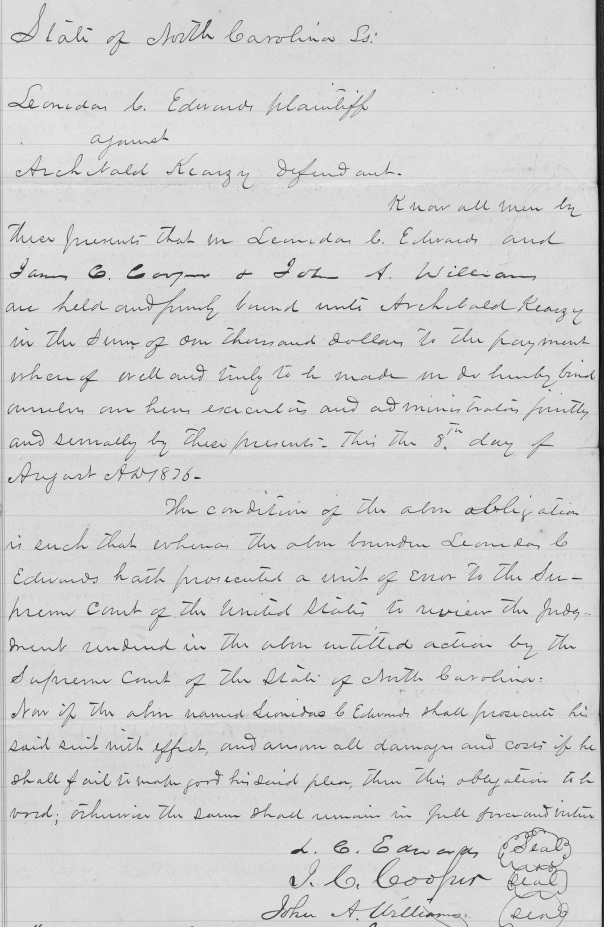

Col. Edwards and his attorneys were able to successfully appeal this case to the United States Supreme Court and posted a $1,000 bond. They argued that this case had federal implications because North Carolina’s Homestead law violated the constitutionality of contracts. In other words, they argued that contracts could no longer be enforceable and would lose value due to what they saw as the overreaching retroactive aspects of the Homestead law.

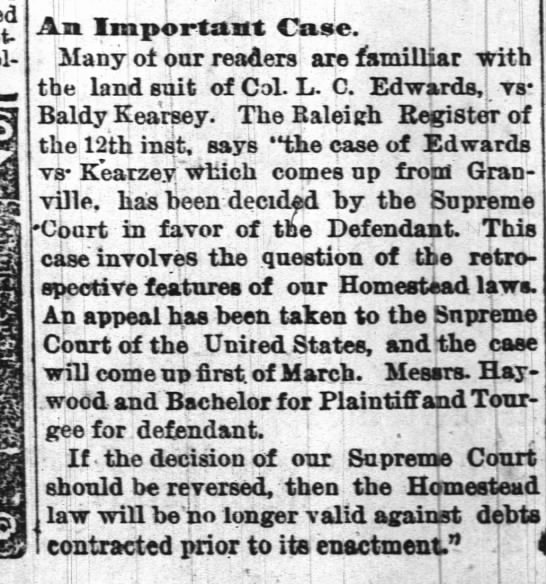

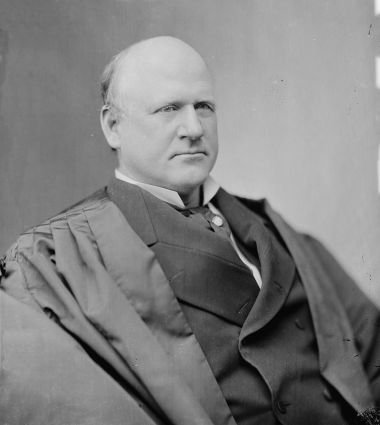

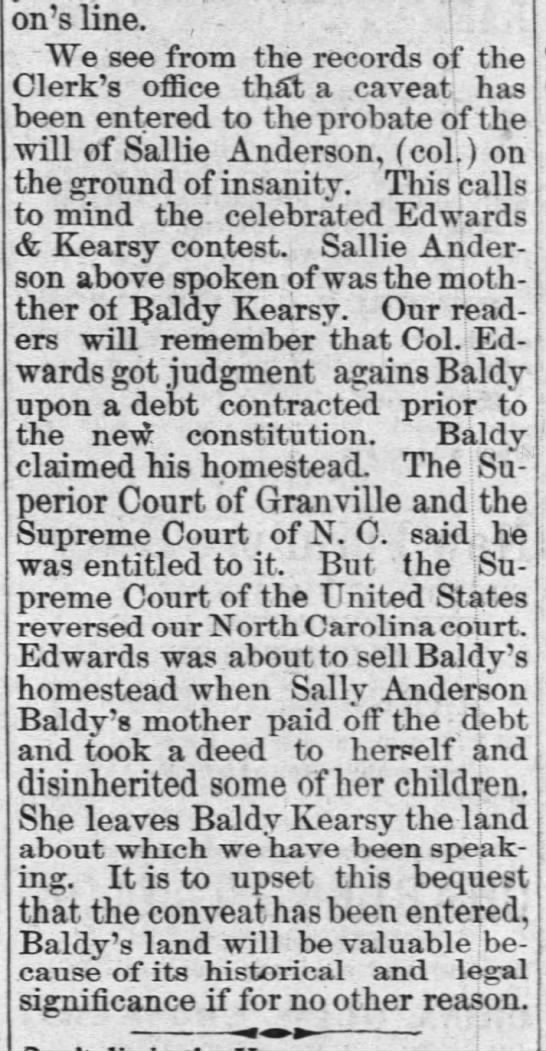

Edwards V. Kearzey, 96 U.S. 595 (1877) is the United States Supreme Court case that issued the final ruling for this case. The implications of the decision were monumental. A newspaper article from the time provides some context:

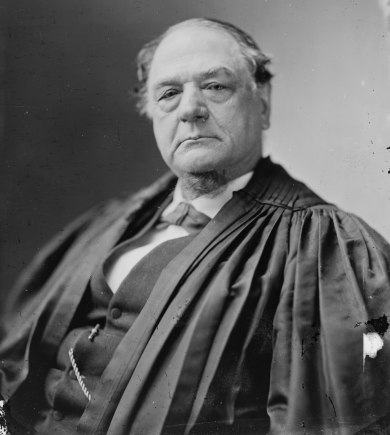

Justice Swayne delivered the majority opinion of the Supreme Court and he reversed the ruling of the North Carolina Supreme Court. You can read a transcribed version of his decision here. In his opinion, he provides an in depth discussion about contract law and cites previous cases. He points out that the United States Constitution states that:

no State shall pass any . . . law impairing the obligation of contracts.

Justice Swayne also offers a definition for a contract:

A contract is the agreement of minds, upon a sufficient consideration, that something specified shall be done, or shall not be done.

When reading up on Justice Swayne, I can see it is no surprise that he ruled in the favor of Col. Edwards. In an earlier U.S. Supreme Court Case, Gelpcke v. Dubuque 68 U.S. 175 (1864), Justice Swayne also found that Iowa could not enact state laws which retroactively impaired contracts.

Justice Clifford and Justice Hunt concurred with Justice Swayne’s decision, and Justice Harlan dissented. Justice Harlan was known as the “Great Dissenter” because of his famous dissents including two of the biggest Civil Rights cases of his time: Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883) and Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896). In both cases the majority opinion of the court sided with the states’ segregation laws but Justice Harlan dissented arguing for equal rights for all.

With the United States Supreme Court ordering ruling in favor of plaintiff Col. Edwards and reversing the lower court’s decision, the court then would need to provide direction on how to resolve the case based upon their ruling.

But…did you really think the fight for Baldy Kersey’s land was over yet?

Baldy Kersey’s Land After the Court Cases

Unfortunately I do not have many records that explain in great detail exactly what happened next. However from an 1883 newspaper article we learn that Col. Edwards was in the process of selling Baldy’s land when Baldy’s mother Sallie Anderson, paid off Baldy’s debt and put the land in her name. At that time, Baldy’s mother Sallie was known as “Sallie Anderson” because she had remarried Martin Anderson.

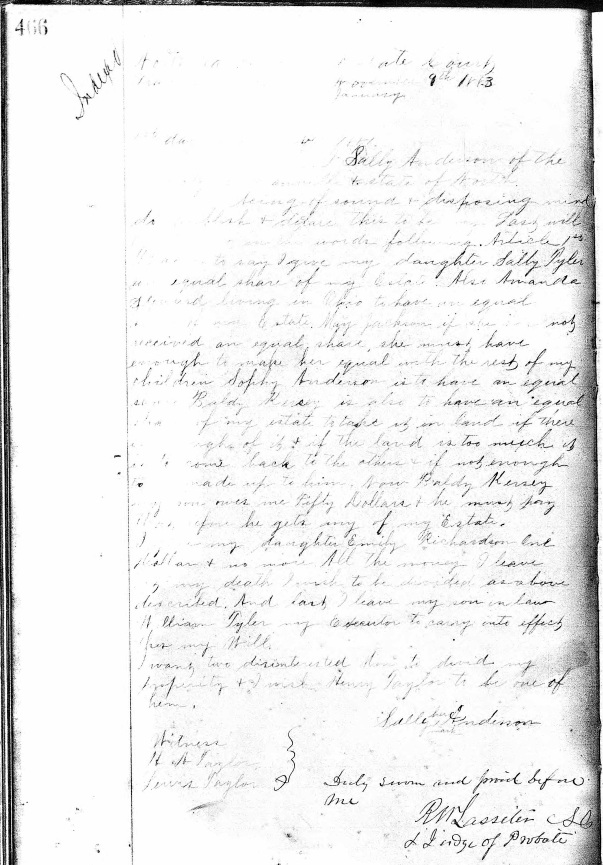

Baldy’s mother Sallie Anderson saved his land and in the 1880 census, Baldy Kersey does appear to be still living on his own land. Though Sallie left the land in his name as specified in her will, we can see from the above newspaper article that her will was being contested on the grounds of insanity.

I found a digitized copy of her will on Ancestry’s North Carolina Probate Records collection. Unfortunately the text is very faded so not all words are legible. However I see her make no mention of disowning any of her children as stated in the above newspaper article. She divided her estate among her children and specifically named her living children at the time: Emily (Kersey) Richardson, Sallie (Kersey) Tyler, Sophia (Kersey) Anderson, and Baldy Kersey. In addition, she left property for Amanda ______ and Mary Jackson. Sallie doesn’t state their relationship to her, but they are named as heirs so perhaps her grandchildren or siblings. In the will, she does leave Baldy her land but also states that he still owed her $50 and that the debt must be paid in order for him to inherit. I wonder if the $50 is related to her paying off his debts to save the land.

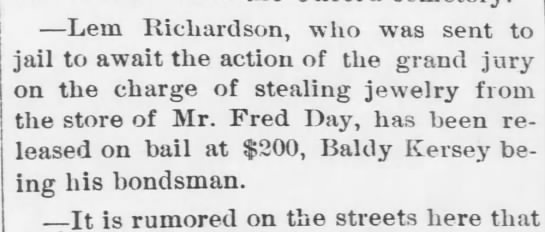

Baldy Kersey continued to appear in the newspaper. On 24 Jan 1890, it was reported in the local paper that Baldy Kersey posted a $200 bond for Lem Richardson to be released on bail on account of being charged with larceny. Lemuel “Lem” Richardson (1867-1922) was the son of Benjamin Richardson and Francis Tyler. Francis Tyler was one of the four children of Martha Jane Tyler that Baldy Kersey had “adopted”. In addition, Baldy Kersey was the brother of Lemuel Richardson’s grandmother Emily (Kersey) Richardson.

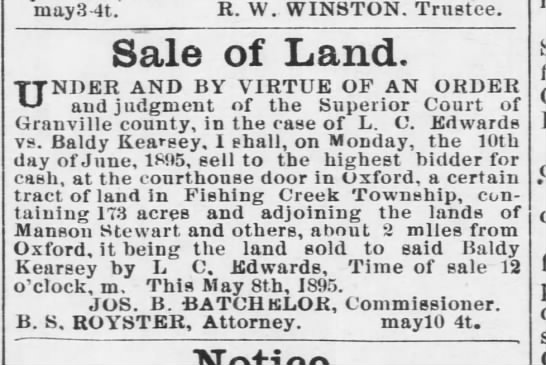

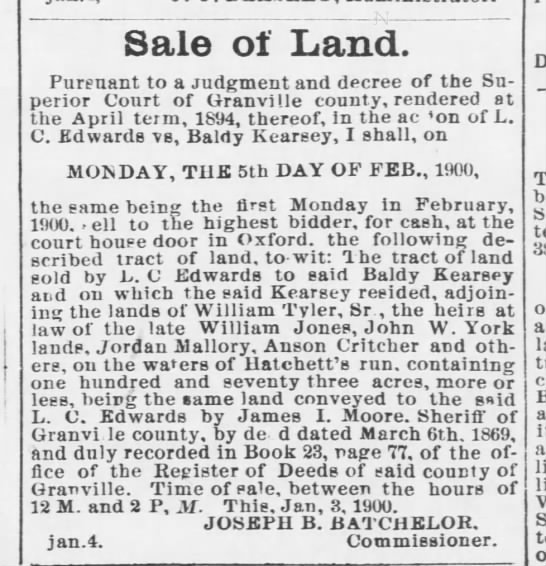

Beginning in 1895, we see that Baldy Kersey’s land was posted for sale. Because the Granville County Superior Court records are not available online, I cannot see the cause for the judgment which lead to the sale. As reported in that earlier newspaper article from 1883, Sallie Anderson’s will was being contested on grounds of insanity. Perhaps her will was successfully contested and as a result, the land was posted for sale.

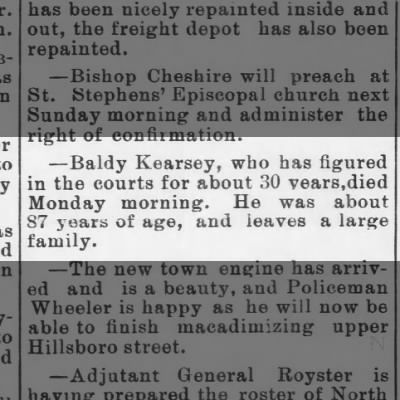

Baldy Kersey died on 20 Nov 1899, where his death was reported in the newspaper a few days later:

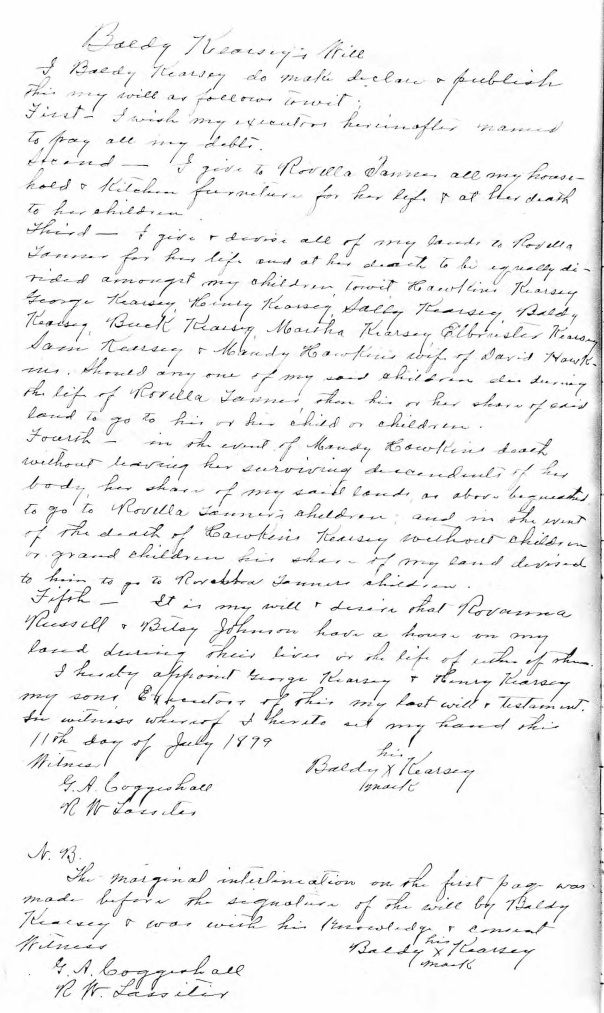

Baldy Kersey left a will in which he left all of his property to his “wife” Rovella Tanner and children (both biological and adopted):

Please send me all this information via email.

LikeLike

Any idea how Monroe ended up there with them in the 1850 census? Also could you email me @ anthonyiz@hotmail.com?

LikeLike

Thanks for all the information…..Keep up the good work.

LikeLike

Kianga you are wonderful. Your research has help our family soooooo much. The Hawleys

LikeLike

Hello cousin we need to find a way to get and find photos from any of the elders of our families

LikeLike

My name is William Taborn and i am the great great grandson of Avery Taborn and Margret Evans. Thank you for providing so much information about my GG grandfather. I would appreciate any information you have on MARGARET Evans and her relationship to Nelly Evans.

LikeLike

Hi William, please email me kiangalucasATgmailDOTcom

LikeLike

I wanted to add few more comments about Avery Taborn and Baldy Kersey. Avery Taborn married Sally Richardson who was Baldy Kersey niece and I believe Avery was still living with Baldy sister Emily Richardson and her husband. I dont have the exact dates but this all could have transpired after Sally Richardson died and Avery left the family.

LikeLike

I am Denise “Nisie” Andrews…great great granddaughter of Avery Taborn and Sally Richardson. After Sally’s death, their sons, William ( 3/1863) and Bennie (1866), resided with their grandparents, Samuel and Emily Kersey Richardson. I don’t know what became of Bennie. His surname was listed as Richardson on the 1870 census. William married Virginia Brandon and died by 1910 (?). Also, Avery is listed in the 1910 census (Boydton, VA). Haven’t found a date of death for him. I admire your work. I am in contact with Bob Tyler. I would sincerely appreciate any info on the Taborns. Many Thanks…

LikeLike

This is absolutely mind blowing. I’m the great great great grandson of Baldy Kersey. Mary Jane Chavis is the great great grandmother. If there is anything more you can find on her or especially her mother Lula Chavis please share or put me on the path of how I can obtain it. Thank you the Hawley-Shells

LikeLike

This is absolutely mind blowing. I’m the great great great grandson of Baldy Kersey. Mary Jane Chavis (1857-1929 is my great great grandmother. If there is anything more you can find on her or especially her mother Lula Chavis please share or put me on the path of how I can obtain it. Thank you the Hawley-Shells

LikeLike

Hi Kianga, I am the great great granddaughter of Mary Jane Chavis Hawley (Bawleys daughter), son Dock or Chester Hawley and great grand of Pattie Richardson Hawley, daughter of Mary and Benjamin. If you have any dire ct information concerning them it would be most appreciated. What I have read so far, it gas opened my eyes. Thank you

LikeLike

Hello!

I have communicated over the years with a few of your cousins who also descend from Mary Jane Chavis Hawley. Thank you for reading the blog. Something that I continue to work on is researching who Lula Chaivs (mother of Mary Jane Chavis Hawley) was and who her parents were. When I’m able to firmly answer that with documentation, I will make a blog post.

LikeLike

Hello all in some form or fashion we are all kin some kind of way. Now as for myself I have no clue where I stand or who I’m kin too, my name is Latoria kersey, grandfather James Kersey grandmother Priscilla Enoch of “Little Texas” (Alamance County) NC. I would love to know how I can get in more depth of my history!!

LikeLike

Hello. New to blog but happy I found it. Excited to see any and all family information no matter what family it is. I’m from SC and sure to be related throughout the northern state as well as other states. Thanks and happy posting Sheila

LikeLike